In the renaissance, the ideas of antiquity became popular again. The first universities were founded in Upper Italy, later on also in other parts of Europe (Leiden, Montpellier, Heidelberg, etc.). Botanical research was still mostly done in the service of medicine. After the invention of letterpress, scientific literature became accessible to a broader public. The 16th century saw thus a new spreading of botanical knowledge including the publications of a number of floras of different countries.

The voyages of discovery that began during the middle of the 15th century brought new plant species to Europe. Among them were a lot of those edible and semi-luxury foods common to us today.

With the beginning of the 14th century, a new cultural movement spread across Europe starting in Florence. The renaissance was the rebirth of the ideas of antiquity. The doctrinal way of thinking that was embodied by scholasticism was done away with and the classical body of thought was begun to be understood. It was based on, further developed and perfected. In Upper Italy, the first universities were founded and with them the first botanical gardens of the modern age: Padua (1543 or 1544), Pisa (1545) and Bologna (1567).

In the remaining part of Europe the first universities were founded in Leiden (1577), Montpellier (1593) and Heidelberg (1597). It was their influence that redirected the attention from the study of plants through books to the examination of living plants. The central focus of research was on one hand the respective flora, on the other hand foreign plants that were cultivated in the botanical gardens. The garden of Pisa was layed out by LUCA GHINI (1490 - 1556). He is attributed the credit of having been the first to press and dry plants in order to conserve them in herbaries. The oldest still existing herbary stems from his pupil CIBO (1532). Botanical research took place mainly at the universities, but was almost exclusively done in the service of medicine. That situation continued up until the 19th century, although the first professor of botany, F. BONAFIDE, was already appointed in Paduain 1533 .

Scientific literature was far more and far easier spread after the invention of letterpress by J. GUTENBERG (Mainz, 1446). The number of reviewed plant species increased rapidly:

Among the outstanding German botanists were

| OTTO BRUNFELS [1488 (Mainz) - 1534 (Bern)]; teacher and physician | |

| HIERONYMUS BOCK, lat. TRAGUS [1498 (Heiderbach) - 1554 (Zweibrcken)]; teacher, attendant of the ducal garden of Zweibrcken, finally physician and priest |

|

| LEONARD FUCHS [1501 (Wemding) - 1566 (Tbingen)]; physician, professor of medicine, first at Ingolstadt, then at Tbingen |

K. SPRENGEL honoured these three botanists in his book "Geschichte der Botanik" (A History of Botany) as being the fathers of German botany.

OTTO BRUNFELS was the first to publish an extensive collection of indigenous plants, depicted after living plants in a printed (!) version. His work was first published in Latin and shortly afterwards in German, too ("Contrafayt Kreutterbuch"). The content is clearly influenced by DIOSCORIDE.

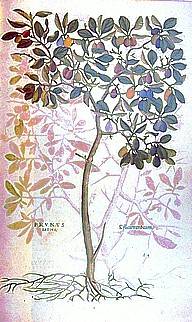

HIERONYMUS BOCK made extensive botanical excursions to the Hunsrck, the Eifel, the Ardennes, the Vosges, the Jura, the Swiss Alps and the countries of the Rhine. He collected plants and cultivated his private garden in order to study their relations. In naming, he followed antique examples and thus drew many wrong conclusions. He maintained a lively correspondence with BRUNFELS. His work was published in 1539. It is called

"New Kreutterbuch von unterscheidt, wrckung und namen der Kreutter, so in Teutschen landen wachsen." (A New Book on Herbs that Grow in German Countries with Special Regard Paid to Their Differences, Their Effects and Their Names.)

The first edition contained no illustrations. The second edition was published in 1546 and was illustrated with 465 wood engravings, many of which had been copied from the works of BRUNFELS and FUCHS. The significance of the work lies mostly in the description of plant structures, as well as in that of their developement in the course of the vegetation period. Besides, elaborate descriptions of the places where the plants were collected are given.

LEONARD

FUCHS saw his main task in the ending of the intellectual rein practised

by the Arabs, especially in the subjects of medicine and pharmacology. He

wanted the great masters of ancient Greece to be remembered. To gain knowledge

of plants, he recommended the study of nature. His work "De historia

stirpium commentarii", published in 1542, belongs to the classical

works of botanical literature. The plant species were listed in alphabetical

order. With FUCHS, too, the text pays reference to DIOSCORIDE. The South

American Onagracean genus Fuchsia is called after him.

LEONARD

FUCHS saw his main task in the ending of the intellectual rein practised

by the Arabs, especially in the subjects of medicine and pharmacology. He

wanted the great masters of ancient Greece to be remembered. To gain knowledge

of plants, he recommended the study of nature. His work "De historia

stirpium commentarii", published in 1542, belongs to the classical

works of botanical literature. The plant species were listed in alphabetical

order. With FUCHS, too, the text pays reference to DIOSCORIDE. The South

American Onagracean genus Fuchsia is called after him.

The description and the search for the meaning of flowering and fruits is neglected by all three researchers.

With the 16th century, botanical knowledge began to spread. It did not remain the priviledge of a few. A number of local floras and of floras of different countries were published. During the 17th century, special regard was paid to German local floras:

We'll mention only a few of the researchers of these times. Today, their names are often found in the families«, generas« or species« names of modern nomenclature (according to LINN).

G.

GESNER (1516 - 1565); named after him are: Gesneriaceans, Gesneria,

Tulipa gesneriana. He was the first to pay closer attention to flowers

and fruits. He depicted them repeatedly and noticed their value for the

classification of the relation of different plants. When he climbed up

the Luzerner Hausberg (the Pilatus), a mountain, he noticed that the flora

was divided into zones according to the different altitudes:

G.

GESNER (1516 - 1565); named after him are: Gesneriaceans, Gesneria,

Tulipa gesneriana. He was the first to pay closer attention to flowers

and fruits. He depicted them repeatedly and noticed their value for the

classification of the relation of different plants. When he climbed up

the Luzerner Hausberg (the Pilatus), a mountain, he noticed that the flora

was divided into zones according to the different altitudes:

| region of eternal winter | |

| region of spring: here, plants that flower already in spring in the plain are flowering in the middle of summer, like violets, coltsfoot or butterbur | |

| region of the summer: valleys and plains | |

| region of autumn: some trees, especially cherries, develop fruits |

In this last region all seasons occur. The third region has in addition

to spring, some winter and some autumn. In the second one a long winter

is followed by a short spring, but in the uppermost region rules everlasting

winter. GESNER observed, too, that the plants of the mountains differed

from those of the plain in that they had smaller and sturdier leaves.

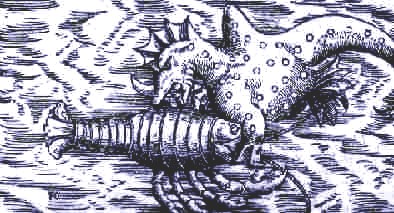

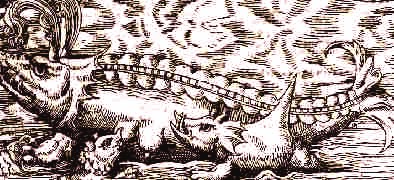

Monsters - from: CONR. GESNERI: Historiae Animalium, Liber IV - Qui est de Piscinum & Aquatilium Animantium natura. - Frankfurt 1620

P. A. MATTHIOLI from Siena (1501 - 1577); named after him are: Matthiola [Cruciferae]. He wrote a book upon herbs that was published until its 60th edition (in Latin) and was translated into Italian, German, and Bohemian.

A. LONICER [1527 (Marburg) - 1586], professor, later physicist of the town Frankfurt. Named after him is the genus Lonicera [Caprifoliaceae]. He, too, wrote a book on herbs that was published troughout five editions.

M. DE L«OBEL (LOBELIUS) (1538, Lille in Flanders - 1616). Named after him is the genus Lobelia [Lobeliaceae]. He was the first to describe some of the groups (families, orders, genera) that are still valid today: grass plants, lilies, rushes, sedges, labiatae, leguminosae and others. He found out that monocotyledons are an independent group and thus emphasized the importance of natural relations.

Among the discoverers of foreign countries were, since the middle of the 15th century the Portugese who travelled along the coast of western Africa. Ceylon, China and finally both continents of America became targets of further voyages of discovery. Many foreign plants found their way into European gardens and a lot of those edible plants and semi-luxury foods common to us today were imported at that time.

The leading Italian botanist of his time was A. CESALPIN(O) (lat. CAESALPINUS) from Arezzo (Tuscany) who lived from 1519 to 1603. He was professor at Pisa and published his main work "De plantis" (Of Plants) in 1583. It was new in many respects, stayed a work of reference for centuries and had a major impact on C. v. LINN. It offers a wide description of theoretical botany with the branches morphology, anatomy, biology, physiology, systematics and nomenclature. Contrary to the works of BRUNFELS, BOCK, and FUCHS, CESALPIN used empirically gained material as the basis for theoretical reflections. He tried to find the general principle that lies behind the single observation and to understand the principally important in the sense of ARISTOTLE. When reviewing plants, he used physiological principles. He compared seeds and buds and tried to proof that the essential part of the seed could be found at that part of the seed, where the cotyledons have their origin. He described flowers as the involucre of the pollination parts. He subdivided flowers into three parts: folium (the calyx, that he regarded as leaves; folium (lat.):leave), stamen and flocci. The last two terms did not have the meaning they have today, for he thought the style to be the stamina and the flocci to be the stamens. CESALPIN wrote that there existed different genders with some plants like hemp, nettle or mercury, but in general this could be neglected, because plants just had too simple a structure. The calyx was seen as a protrusion of the bark and CESALPIN thus thought that it would outlive the flower. He pointed out that in classifications not only the differences of the fruit had to be taken into account, but those of the flower and the calyx, too. But he thought colour, scent and taste to be of no importance and recommended to pay no attention to them.

His system of plants was based on the different structures of the fruits. The classical organisation of THEOPHRASTUS, that grouped plants into trees, shrubs and herbs was still superordinated:

- Trees. A. those with only one seed per fruit, B. those with two compartments for the seeds, C. those with three compartments, D. those with four and E. those with many compartments

- Shrubs and herbs. A. single-seeded ones, B. two-seeded ones, etc

- Seedless plants (fern, moss, algas)

CESALPIN was not uninfluenced by scholastic ideas. He wrote longwinded passages about the problem of the soul and asked, whether two souls existed in every plant: one in the roots and one in the shoot. He answered this question by deciding that only one soul existed that lived in the root near the soil line.

|

|