How plants conquered the land

Fossils tell the story

About fourhundred and fifty million years ago, at the end of the Ordovician

and in the beginning of the Silurian, the land was desolate and empty. Barren,

hardly wethered rockgrounds, empty sand-, gravel- and clayplains, no green.

Maybe some lichens. And at wet spots some algues with a couple of spider-like

little creatures creeping around. In the neighbourhood of the mouth of rivers,

where the water regularly flooded the land, it was probably green with algues.

At such places, e.g. in Australia, traces of big seascorpions have been found.

There was not much happening on the land. Life enacted itself nearly completely

in the water.

Cooksonia

The first fossils of real land plants have been found in the Middle

Silurian of Ireland. They are about 420 million years old. They consist of

small bifurcations some centimeters in size. Only in the very last part of

the Silurian fossils of land-plants become

more common and also more

complete. The best known plant from that time is called Cooksonia. It is

named after Isabel Cookson, who occupied herself with intensive collecting

and describing plantfossils. more common and also more

complete. The best known plant from that time is called Cooksonia. It is

named after Isabel Cookson, who occupied herself with intensive collecting

and describing plantfossils.

The little plant looked very simple: a stem which bifurcated a couple of

times topped with small spheres in which the spores were formed. Thus sporangia.

No leaves, no flowers, no seeds. And roots? Probably horizontal growing stems,

connected with the soil by root hairs, took the function of roots. But this

is not sure for fossils proving this have not been found yet.

During many millions of years it was mainly this kind of plants that grew

on humid places on the land.

The evolution from algues to land plants must have been a lengthy process.

Many conditions had to be fulfilled before plants were able to maintain

themselves on the land. There is at first the everlasting danger of desiccation.

The remedy which developed is a thin waxy layer at the surface of the plant:

the cuticle. Generally algues don't have a cuticle, nearly all land plants

do.

But a land plant also has to breath and it needs the possibility to assimilate

carbondioxide from the air to generate its nutriments. Thus the isolation

by the cuticle can not be absolute. That's why the stomata have evolved,

which can be opened and closed if necessary.

Another problem for land plants is that they miss the upward force of the

water. To be able to keep upright supporting tissue is needed. Already in

Cooksonia xylem vessels have been recorded. These are vessels with

annular or spiral shaped thickenings at the walls, which give them solidity.

Through these vessels water is transported from the soil to the plant cells.

Another problem for land plants is that they miss the upward force of the

water. To be able to keep upright supporting tissue is needed. Already in

Cooksonia xylem vessels have been recorded. These are vessels with

annular or spiral shaped thickenings at the walls, which give them solidity.

Through these vessels water is transported from the soil to the plant cells.

Another important adaptation to landlife is the very tough wall that evolved

around the spores. This provided the spores with an excellent protection

against desiccation, fungi, and so on. In fact they became nearly invulnerable,

for they have been fossilised very often.

Species of Cooksonia are found at several places on earth, e.g.

in Wales, Scotland, England, Czechia and Canada. The finding of a fairly

complete plant is a rare occurrence. I was already very glad with the bifurcated

little stem with two sporangia between Cooksonia-chaff on the photo.

Cooksonia has become extinct in the Early Devonian.

Enigmatic plants

At the time of the first Cooksonias a completely different group

of plants has evolved, which tried to colonize the land. These plants are

still enigmatic for scientists. Research for the real nature and the ecology

of these plants is still in full progress. We shall mention three of them

(there are more): Nematothallus, Parka and Pachytheca.

Fossils

of Nematothallus look like black patches measuring 0,5 to 6 cms. They

are irregular in shape and sometimes there is still a thick cuticle on the

plant. It is possible to make a microscopic preparation of a piece of cuticle

and in some cases it turns out to have a cell structure. As this has not

developed in the way of cell division in higher plants it is called pseudo

cell structure. Under the cuticle is a little mat consisting of very thin

threads or tubes. The diameter of such a tube varies from 3 µms to 40

µms (1 µm = one thousandst of a millimeter). Spores have also been

found in the mats. Apparently Nematothallus did consist of a thallus

of fine threads (Gr. nemato = thread) covered by a thick cuticle, sometimes

with a pseudo cell structure. Plants like these do not exist any more, however

there are recent lichens resembling Nematothallus in several aspects. Fossils

of Nematothallus look like black patches measuring 0,5 to 6 cms. They

are irregular in shape and sometimes there is still a thick cuticle on the

plant. It is possible to make a microscopic preparation of a piece of cuticle

and in some cases it turns out to have a cell structure. As this has not

developed in the way of cell division in higher plants it is called pseudo

cell structure. Under the cuticle is a little mat consisting of very thin

threads or tubes. The diameter of such a tube varies from 3 µms to 40

µms (1 µm = one thousandst of a millimeter). Spores have also been

found in the mats. Apparently Nematothallus did consist of a thallus

of fine threads (Gr. nemato = thread) covered by a thick cuticle, sometimes

with a pseudo cell structure. Plants like these do not exist any more, however

there are recent lichens resembling Nematothallus in several aspects.

Fossils of Nematothallus have been found in formations from the Middle

Silurian up to and including the Early Devonian. In Great-Britain they are

found in several places.

A second enigmatic

plant is Parka. This is a flat, circular to irregular patch covered

by discs about 2 mm wide. These are sporangia each containing some 35,000

spores. The diameter of this plant varies from 0,5 cm to 7 cms. Where the

sporangia have disappeared from the fossils, and this is often the case,

a kind of reticulum remains. For a long time Parka has been supposed

to be a collection of some animal's eggs. Especially in the region of Forfar,

north of Dundee in Scotland, Parka is very common. A second enigmatic

plant is Parka. This is a flat, circular to irregular patch covered

by discs about 2 mm wide. These are sporangia each containing some 35,000

spores. The diameter of this plant varies from 0,5 cm to 7 cms. Where the

sporangia have disappeared from the fossils, and this is often the case,

a kind of reticulum remains. For a long time Parka has been supposed

to be a collection of some animal's eggs. Especially in the region of Forfar,

north of Dundee in Scotland, Parka is very common.

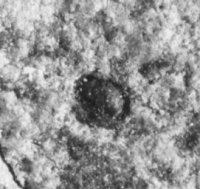

The third still unelucidated plant

is Pachytheca. This fossil resembles a gleaming little globe with

a diameter between 1 and 7 mms. In transverse the sphere has an outer layer

with radial tubes and a nucleus in which the tubes are going in all directions.

For a long time Pachytheca was thought to be part of a bigger plant,

but nowadays it is firmly believed to be a complete organism. The fossils

have been found in e.g. Belgium and Great-Britain. This plant too became

extinct in the Early Devonian. The third still unelucidated plant

is Pachytheca. This fossil resembles a gleaming little globe with

a diameter between 1 and 7 mms. In transverse the sphere has an outer layer

with radial tubes and a nucleus in which the tubes are going in all directions.

For a long time Pachytheca was thought to be part of a bigger plant,

but nowadays it is firmly believed to be a complete organism. The fossils

have been found in e.g. Belgium and Great-Britain. This plant too became

extinct in the Early Devonian.

Probably these and similar alguelike plants can be considered as an

evolutionary experiment to colonize the land. It seems having been a dead

end. It is not unlikely that these plants have lost the increasing competition

with the succesful higher plants.

Top |