A Profile of

Ethnobotany in Africa:

Results of an Africa-wide

survey

(R.Höft &

M.Höft)

In the last few years, ethnobotany has

gained momentum as a scientific

discipline in Africa. Increasing

population pressure conflicting with

restriction of access to limited plant

resources has been calling for new

approaches in resource management.

Researchers and development workers from

a number of backgrounds have drawn

methods from various scientific

disciplines, modified and merged these

into what can now be considered a package

of ethnobotanical methods. Involving all

partners, applied ethnobotany has a

potential to respond to the acute needs

and concerns of people faced with the

rapid deterioration of their natural and

cultural heritage.

In the following we attempt to provide

a picture of the current situation of

ethnobotany in Africa by evaluating a

questionnaire which has been filled in by

more than 200 African ethnobotanists

prior to the establishement of an

Africa-wide network of ethnobotanists.

The XVth AETFAT (Association for the

Taxonomic Study of the Tropical African

Flora) Conference held in February 1997

in Harare was an important occasion for

many interested botanists and

ethnobotanists to discuss priorities and

working methods of this Network.

Objectives

of the African Ethnobotany Network (AEN)

The African Ethnobotany Network (AEN)

aims at harmonizing the efforts of

individuals and small teams who

contribute through research, education,

provision of field training, various

means of sharing information, and the

improvement and diversification of

existing ethnobotanical methods to the

recognition of ethnobotany as scientific

discipline and as an appropriate

technical tool in the management of plant

resources. The AEN does, thereby, not

intend to compete with other specialized

groups with overlapping interests (such

as the AETFAT, the Indigenous Plant Use

Forum (IPUF), the Southern African

Botanical Diversity Network (Sabonet), or

the IUCN/SSC Medicinal Plants Specialist

Group) but to collaborate with these

wherever possible. At the same time, it

can provide a service to individuals who

feel the need for material and

information additional to those available

within the existing networks.

To encourage the start of an African

Ethnobotany Network and to create some

fundament for reference, a questionnaire

was sent to the members of AETFAT

(Association for the Taxonomic Study of

the Flora of Tropical Africa) and to the

African ethnobotanists in contact with

the People and Plants Initiative of WWF,

UNESCO and the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.

By 1 September 1997, about 300 recipients

had responded with the large majority

wishing to participate in the African

Ethnobotany Network. Additional replies

have arrived after this date. The current

Network membership list is included at

the end of this Bulletin.

Evaluation

of questionnaires

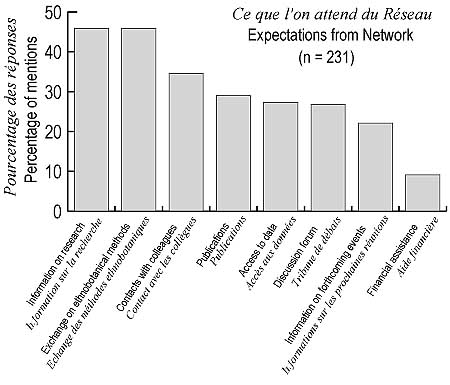

From the questionnaires, it would

appear that equal importance was accorded

to the information of ongoing and past

research and to the exchange of

ethnobotanical methods (Figure 1). Of

lesser importance, but nevertheless

mentioned by 10% of respondents, was the

desirability of financial assistance.

|

Figure 1

|

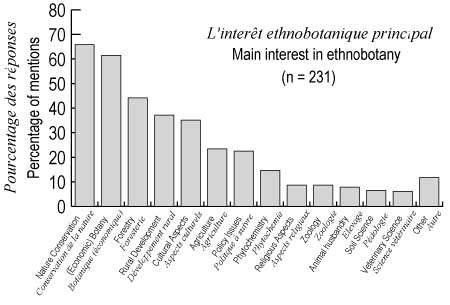

Answers with respect to

the main interest related to the

interdisciplinary field of ethnobotany

reflected the priority of conserving and

sustainably managing natural resources. A

majority of the respondents mentioned

nature conservation together with botany

or economic botany as their prime

interest (Figure 2). Among the more

important fields (< 30%) figured

forestry, rural development and cultural

aspects. Religious aspects, zoology,

animal husbandry, soil science and

veterinary sciences were mentioned by

less than 10% of the respondents.

|

Figure 2

|

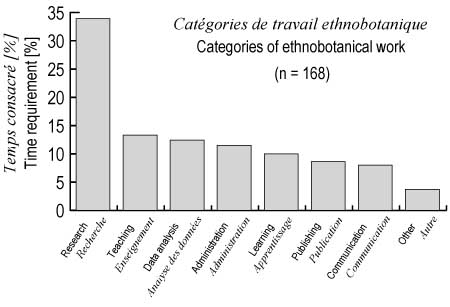

Among 100 respondents

who estimated the percentage of their

time allocated to ethnobotanical work the

average was 33%. The teaching load being

heavy for most university-based

researchers, and administrative tasks

sometimes limiting the length of field

stays, it was interesting to get an idea

of the time allocation for different

categories of ethnobotanical work, such

as research, teaching, data analysis,

administration, learning, publishing and

communication (Figure 3). While only 168

of the 231 respondents answered this

question, it would appear, that the time

spent for research by far exceeded the

time for teaching and data analysis. Time

spent on data analysis was a mere 12% and

the allocation for writing/publishing

less than 10%. Of course, these figures

are estimates, but it may be fair to say

that an increased awareness about

analytical tools and quantitative methods

in ethnobotany is likely to lead to a

relative increase of the percentage of

time required for data analysis and

presentation.

|

Figure 3

|

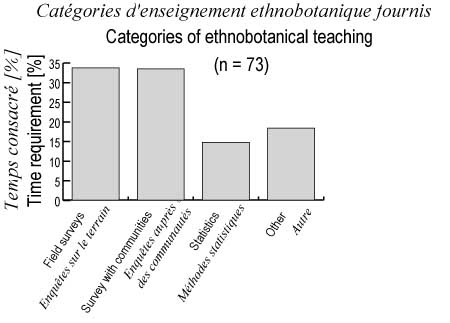

Even fewer respondents

(n=73, Figure 4) gave details on their

teaching. When looking into the

categories of training provided by

participants of the AEN, field surveys

and surveys with communities were clearly

the most common (ca. 33%), while only 15%

(i.e. 11 people) appear to use statistics

in their teaching programme. This agrees

with the small percentage of time spent

on analysis of ethnobotanical data (see

Figure 3).

|

Figure 4

|

Among 107 academic

staff who responded, the average number

of students trained in ethnobotany was

14. Consequently, and discounting

multiple scoring of individual students,

each year about 1500 African students are

learning about ethnobotany according to

this limited survey. While this figure is

encouraging, it does not indicate the

position ethnobotany takes within the

overall curriculum, particularly while

there are still very few institutions

that provide formal curricular courses in

ethnobotany.

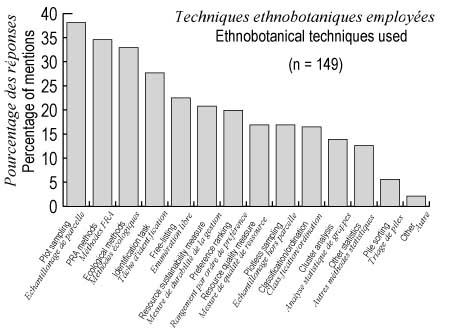

The situation of ethnobotany as a

multidisciplinary science which draws

methods from various academic fields and

subjects is reflected by the large number

of techniques used regularly by the

respondents (Figure 5). Although the

techniques listed may overlap, the

answers were classified in 14 different

categories. About one third of the

respondents mentioned plot sampling,

Participatory Rural Appraisal methods

(PRA) and general ecological methods

(e.g., population analysis, vegetation

analysis, soil sampling), followed by

more typically ethnobotanical techniques

such as identification tasks and

free-listing. A number of quantitative

techniques for applied research projects

included the application of resource

sustainability measures (i.e. analysis of

resource regrowth versus extraction

rate), preference ranking and resource

quality measure (distinction on the basis

of individual plants on the

appropriateness for a certain use).

Plotless sampling and multivariate

methods developed for vegetation

analysis, such as classification and

ordination (16.5%), cluster analysis

(13.9%) or other statistical methods

(12.6%), appeared to be less popular.

|

Figure 5

|

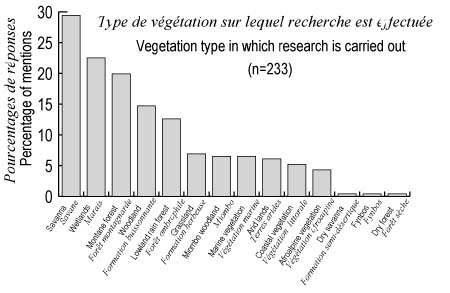

Participants were asked

to indicate in which vegetation type they

carry out ethnobotanical research to get

an overview of the relative importance

attributed by ethnobotanists to the major

vegetation units (Figure 6). Almost one

third of the 159 respondents work in

savanna areas. Relative to their extent,

wetlands, montane forests, lowland rain

forests and Afroalpine vegetation are

important targets for ethnobotanical

research.

|

Figure 6

|

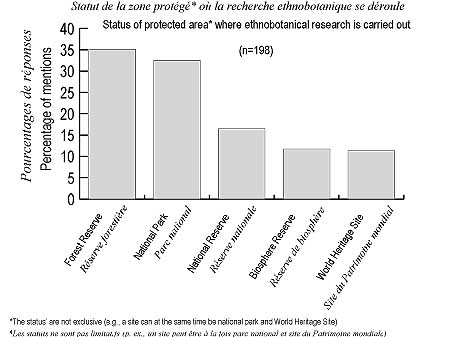

It was also interesting

to note that almost 50% of the ongoing

ethnobotanical research is carried out in

protected areas. Forest Reserves and

National Parks figured more prominently

(< 30%) than National Reserves,

Biosphere Reserves and World Heritage

Sites (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7

|

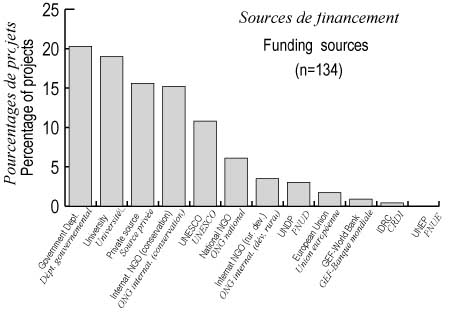

Twelve principal

agencies were identified for funding

projects of 136 respondents (Figure 8).

Governmental departments and universities

ranked highest with ca. 20% of all

projects funded, followed by private

sources and international NGOs engaged in

conservation with ca. 15% each. Among the

UN agencies, UNESCO and UNDP were

mentioned while UNEP did not provide

funding to any of these projects.

Naturally, a large number of projects

funded by any single organization does

not necessarily imply that the total

amount provided is high. From this

survey, the budget spent annually on

ethnobotanical work in Africa adds up to

about 3 million US dollars.

|

Figure 8

|

To date more than 250

respondents have expressed their interest

in participating in the AEN. In view of

the fact that of this number only about

half are doing ethnobotanical research or

teaching the question arises whether the

AEN will develop to serve an increasing

number of vaguely interested people or

whether it will develop with the support

of active and engaged participants into a

powerful source of applied ecological

science for conservation.

Setting-up of the

African

Ethnobotany NetworkA workshop held

during the AETFAT Conference in Harare in

February 1997 provided a first forum to

discuss the expectations from such a

Network and to complement the picture

that arose from the evaluation of answers

provided by respondents to the

questionnaire.

The AETFAT workshop felt that the

central objective of an African

Ethnobotany Network should be to

facilitate the exchange of information

and experience. As many African

researchers have as yet no access to

electronic information exchange and

depend on poorly equipped libraries,

access to relevant literature and thus

the awareness of ongoing research and

useful methodologies is limited. This

situation could be improved by sharing

documents and exchanging literature

within a functioning Network. On the

basis of the need identified at the

AETFAT workshop and the postal survey

(see Figure 1), Tony Cunningham has

prepared a review of ethnobotanical

publications from eastern and southern

Africa which is part of this Bulletin.

The African Ethnobotany Network should

furthermore help develop the contact

between colleagues who have similar

interests, use the same methodologies or

undertake work that is complementary to

the work of others. It could thereby

facilitate exchange among individuals and

projects and help stimulate and shape

joint undertakings of various kinds.

While a strong Network could eventually

provide some support for raising

resources for applied research projects,

the Network itself should essentially

function on a voluntary basis.

The Network should raise awareness

about ethical issues, such as

Intellectual Property Rights, resource

access rights and the patenting of

Indigenous Knowledge. In informing about

approaches used to protect local

knowledge, community land rights and

access to biological resources the AEN

could contribute to increased awareness

among local people, researchers and

policy-makers. In concrete terms this

could imply a more common use of

contractual agreements with respect to

private commercial use of indigenous

plant knowledge. It should also make it a

basic principle for ethnobotanists to ask

who would benefit from their work, to

seek agreements with elders in charge of

safekeeping communally owned sacred sites

before embarking on field research and to

publish only the results that are agreed

to become "shareware".

Common concern was expressed about the

need for close collaboration and

consultation of the existing information

among members from the beginning of each

undertaking, to avoid duplication of

efforts on the one hand and to focus

efforts, e.g., on areas of high botanical

and cultural diversity, on the other

hand. Increased recognition of

ethnobotany as a scientific discipline

was rated highly desirable, but the need

was also recognized to further validate

existing methods and define common

concepts, e.g., concerning the term

ethnobotany itself.

AEN

secretariat

A number of points were identified by

participants in the Harare workshop of

how the AEN could maximize its impact.

These include the identification of

national focal points, working groups or

projects, the preparation and

distribution of publication lists and the

availability of regularly updated address

lists or data files of members of the

AEN.

A preliminary list of focal points has

been established, which, however, needs

reconfirmation, since some potential

focal points did not attend the workshop

and some countries were not represented.

An interim secretariat is currently

provided by UNESCO, through interested

members of staff. While UNESCO Offices in

Nairobi and Dakar, both of which have

some capacity and expertise in the fields

of ethnobotany and ecology, showed

interest in contributing to such a

service, a longer-term commitment has not

been made. Clearly, in addition to the

country focal groups, a functioning

secretariat will be indispensable to

ensure the overall co-ordination of the

Network. Tasks of the secretariat may

include the following:

- compile and distribute up-to-date

information on who is doing what

beyond the national scale. This

is already well established in

South Africa, through the

Indigenous Plant Use Network

(Hale et al., 1995; see

bibliography below), but less so

in other African countries;

- distribute relevant literature;

- review ethnobotanical project

proposals;

- provide information on possible

sources for funding;

- compile, print and distribute a

newsletter.

Country

co-ordinators

A network depends entirely on the

willingness and capacity of its members

to share information and expertise.

Country co-ordinators should, therefore,

facilitate the flow of information

between the secretariat and members of

the network. An initial undertaking will

be to publish an annual newsletter or

bulletin. From then on, much will depend

on the country co-ordinators and the

following comments were made with regard

to their role. The country co-ordinators

should:

- establish a national link among

the people carrying out

ethnobotanical activities;

- compile a list of interested

ethnobotanists in their country

as well as information on their

ongoing projects and keep it

up-to-date;

- raise awareness in their country

about the existence of the

Network;

- provide the link between the

national group and the overall

Network including circulating

information and literature from

the secretariat among the

members;

- co-ordinate activities within a

national working group;

- promote collaborative research

projects of scientists within and

beyond the country;

- facilitate the collection of

ethnobotanical data, and the

organization and publication as

well as distribution of existing

publications;

- keep and gather a list of

publications (old and recent) on

ethnobotany and related topics in

the country and - if possible -

acquire relevant literature and

establish a collection;

- provide a link between local

ethnobotanists and other

countries as well as external

(e.g., European and American)

centres;

- hold regular meetings of the

country working group;

- receive updated information from

other stakeholders and make it

accessible to the appropriate

people and groups;

- contribute to the validation of

ethnobiological data.

Eventually the country co-ordinators

should organize the development of a

written national ethnobotany programme

document which reviews past literature

and on the basis of national capability

and needs, develops a strategic research

plan.These points were not discussed in

detail during the workshop but the above

list reflects a tentative order of

priority. While some of the above

suggestions may be difficult to sustain

given the limitations of time and

resources, others would be only possible

to realize with continued institutional

support. Concern was also raised about

co-ordinators who, for various reasons,

might not perform as the country’s

ethnobotanists would wish. A small

co-ordinating team was therefore proposed

instead of a single co-ordinator. The

addresses of nominated country

co-ordinators are listed at the end of

this document (page 83).

The future

The Network builds on recent

initiatives in the field of ethnobotany,

e.g., the Handbook that was published by

the People and Plants Initiative which

addresses such themes as sharing

information, returning results or the

legal and ethical implications of

enthobiology, and which has been

distributed widely throughout Africa

(Table 1). The Network is intended to

further amplify these efforts.

Much of the future will depend on

individual initiative and the

establishment of functioning national

working groups. Contributions to future

Bulletins and Newsletters are among the

immediate desirable inputs. Monitoring of

membership development and the evaluation

of input from members will help to

foresee future needs and strengthen the

efficacy of the AEN.

|

Amazing and durable

pieces of work are often a result

of joint efforts |

Furthermore, efforts

should be undertaken to generate a solid

methodological basis and validate methods

currently used in ethnobotanical

research. The particular need for

methodological training will be further

addressed through appropriate manuals and

training courses. To this end, it might

be envisaged to constitute a board of

experts who could advise on methodologies

and who would help to ensure that project

proposals correspond to the standards

before being submitted to funding

agencies.

| Table

1. Number of recipients

of the People and Plants Handbook

in Africa by countries |

| Country |

No.

of recipients |

| Angola |

5 |

| Botswana |

5 |

| Burkina Faso |

4 |

| Burundi |

2 |

| Cameroon |

38 |

| Central African

Republic |

1 |

| Chad |

1 |

| Comoros |

1 |

| Congo |

3 |

| Côte d'Ivoire |

3 |

| Democratic Republic

of Congo |

4 |

| Egypt |

1 |

| Ethiopia |

31 |

| Gabon |

6 |

| Ghana |

8 |

| Kenya |

204 |

| Madagascar |

16 |

| Malawi |

16 |

| Mali |

2 |

| Mauritius |

8 |

| Morocco |

5 |

| Mozambique |

9 |

| Namibia |

8 |

| Niger |

1 |

| Nogeria |

20 |

| Senegal |

4 |

| Seychelles |

4 |

| Sierra Leone |

1 |

| South Africa |

84 |

| Sudan |

5 |

| Swaziland |

4 |

| Togo |

1 |

| Uganda |

73 |

| United Republic of

Tanzania |

34 |

| Zambia |

13 |

| Zimbabwe |

31 |

|

|