Medicinal Plant Use

in Africa

The

role of traditional medical practitioners

|

| Photo

1. Trainee diviner

(twasa)

with a small quantity of

Boophane disticha

(Amarylldaceae) bulbs for

local use. |

|

In contrast with western

medicine, which is technically

and analytically based,

traditional African medicine

takes a holistic approach: good

health, disease, success or

misfortune are not seen as chance

occurrences but are believed to

arise from the actions of

individuals and ancestral spirits

according to the balance or

imbalance between the individual

and the social environment

(Anyinam, 1987; Hedberg et al.,

1982; Ngubane, 1987; Staugard,

1985; WHO, 1977). Traditionally,

rural African communities have

relied upon the spiritual and

practical skills of the TMPs

(traditional medicinal

practitioners), whose botanical

knowledge of plant species and

their ecology and scarcity are

invaluable. Throughout Africa,

the gathering of medicinal plants

was traditionally restricted to

TMPs or to their trainees (Photo

1). Knowledge of many species was

limited to this group through

spiritual calling, ritual,

religious controls and, in

southern Africa, the use of

alternative (hlonipha) names not

known to outsiders. |

Hedberg et al., (1982) observed

that the number of traditional

practitioners in Tanzania was estimated

to be 30 000 - 40 000 in comparison with

600 medical doctors (Table

1) (MP and TMP : total population

ratios were not given). Similarly, in

Malawi, there were an estimated 17 000

TMPs and only 35 medical doctors in

practice in the country (Anon., 1987).

Table

1. Ratios

of traditional medical

practitioners (TMPs) and medical

doctors to total population in

selected African countries.

| COUNTRY |

TMP

: TOTAL POP. |

MD

: TOTAL POP. |

REFERENCE |

NIGERIA

Benin City

National average |

1 : 110

? |

1 : 16 400

1 : 15 740 |

Oyenye & Orubuloye,

1983

Gestler, 1984 |

GHANAK

wahu district |

1 : 224 |

1 : 20 625 |

Anyinam, 1984 |

KENYA

Urban (Mathare)

Rural (Kilungu) |

1 : 833

1 : 146 - 345 |

1 : 987

1 : 70 000 |

Good, 1987

Family Health Institute,

1987 |

TANZANIA

Dar es Salaam |

1 : 350 - 450 |

? |

Swantz, 1984 |

ZIMBABWE

Urban areas

Rural areas |

1 : 234

1 : 956 |

?

? |

Gelfand et al, 1985 |

| SWAZILAND |

1 : 110 |

1 : 10 000 |

Green, 1985 |

SOUTH AFRICA

Venda area |

1 : 700 - 1 200 |

1 : 17 400 |

Savage, 1985

Arnold & Gulumian,

1987 |

*

so-called “homeland”

areas only

|

Economic and demographic

projections for most African countries

offer little grounds for optimism. A

shift from using traditional medicines to

consulting medical doctors, even if they

are available, only occurs with

socio-economic and cultural change,

access to formal education (Kaplan, 1976)

and religious influences (e.g. through

the African Zionist movements, which

forbid the use of traditional medicines

by their followers, substituting the use

of ash and holy water instead; Sundkier,

1961). Access to western biomedicine,

adequate education and employment

opportunities requires economic growth.

Unfortunately, most African countries are

affected by unprecedented economic

deterioration. Per capita income has

reportedly fallen by 4% since 1986,

whilst Africa’s foreign debt is

three times greater than its export

earnings. In Zambia, government spending

on education has fallen by 62% in the

last decade, and that on essential

pharmaceutical drugs by 75% from 1985 to

1989 (Zimbabwe Science News, 1989). At

the same time, the African population has

grown by 3% per annum, increasing the

difficulty of adequate provision of

Western-type health services. For this

reason, there is a need to involve TMPs

in national healthcare systems through

training and evaluation of effective

remedies, as they are a large and

influential group in primary healthcare

(Akerele, 1987; Anyinam, 1987; Good,

1987). Sustainable use of the major

resource base of TMPs - medicinal plants

- is therefore essential.

Customary controls

on medicinal plant gathering

The sustainable use of medicinal

plants was facilitated in the past by

several inadvertent or indirect controls

and some intentional management

practices.

|

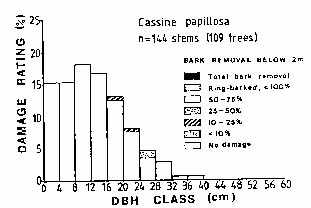

| Figure

1.

Assessment of debarking

damage to Cassine

papillosa (Celastraceae)

trees in an area where

subsistence harvesting

rather than commercial

exploitation is taking

place (Cunningham, 1988a)

|

|

Taboos,

seasonal and social restrictions

on gathering medicinal plants,

and the nature of plant gathering

equipment all served to limit

medicinal plant harvesting. In

southern Africa (and probably

elsewhere) before metal machetes

and axes were widely available,

plants were collected with a

pointed wooden digging stick or

small axe, which tended to limit

the quantity of bark or roots

gathered. For example,

traditional subsistence

harvesting of Cassine papillosa

bark causes relatively little

damage to the tree (Figure 1). |

Pressure on medicinal plant

resources has remained low in remote

areas and in countries such as Mozambique

and Zambia where the commercial trade in

traditional medicines has only developed

to a limited extent due to the small size

of major urban centres. Examples of

factors which have limited pressure on

species which would otherwise be

vulnerable to over-exploitation include:

(1) Taboos against the collection

of medicinal plants by menstruating

women in South Africa and Swaziland;

it is believed that this would reduce

the healing power of the plants

(Scudder and Conelly, 1985).

(2) The tendency in southern

Africa for women to practise as

diviners, while men practise as

herbalists (Berglund, 1976; Staugard,

1985). This limits the number of

resource users.

(3) The perceived toxicity of some

medicinal species which reduced their

use in the past: the level of

toxicity is sometimes given mythical

proportions. Synadenium cupulare for

example, is considered so toxic that

birds flying over the tree are

killed; special ritual preparations

are made in west Africa before the

bark of Okoubaka aubrevillei is

removed (Good, 1987).

(4) The traditional use of a

wooden batten for removal of bark

from Okoubaka aubrevillei - under no

circumstances may a machete or other

metal implement be used (Good, 1987).

For any society to institute

intentional resource management controls,

certain conditions have to be fulfilled:

(1) the resource must be of value

to the society;

(2) the resource must be perceived

to be in short supply and vulnerable

to over-exploitation by people;

(3) the socio-political nature of

the society must include the

necessary structures for resource

management.

Intentional resource management

controls have endured in Africa in

various forms and for various reasons and

some have affected the abundance and

availability of medicinal species. The

widespread practice in Africa of

conserving edible wild fruit-bearing

trees for their fruits or shade also

ensures availability of some traditional

medicines as several are multiple-use

species. For example the following six

trees are conserved for their fruit:

Irvingia gabonensis and Ricinodendron

heudelotii in west Africa (barks are used

for diarrhoea and dysentery); from

southern Africa Trichilia emetica

(enemas), Parinari curatellifolia

(constipation and dropsy), Azanza

garkeana (chest pains), and Sclerocarya

birrea (diarrhoea). Albizia

adianthifolia, used for enemas, is

conserved for its shade.

Protection of vegetation at grave

sites, for religious and spiritual

reasons, is a common feature in many

parts of Africa (including Kenya, Malawi,

South Africa and Swaziland) and an

important means through which biotic

diversity is maintained outside core

conservation areas. In south-eastern

Africa during the nineteenth century,

specific Zulu regiments were called up

annually to burn fire-breaks around the

grave sites of Zulu kings: these woodland

or forested sites were considered to be a

sanctuary for game animals (Webb and

Wright, 1986). An important feature of

vegetation conservation around grave

sites is that this practice is maintained

even under high population densities and

tremendous demand for arable land, for

example in Malawi. The practice might

possibly be strengthened through the

burial of prominent leaders in

conservation areas.

Religious beliefs have also helped to

ensure careful harvesting of Helichrysum

kraussii, an aromatic herb known as

impepho in Zulu which is widely burnt as

an incense in Natal. Diviners are careful

not to rip the plant out by its roots

(Cooper, 1979).

In Swaziland and South Africa, taboos

also restrict the seasonal (summer)

collection of Alepidea amatymbica roots,

Siphonochilus aethiopicus and Agapanthus

umbellatus rhizomes. In each case,

collection is restricted to the winter

months after seed set as summer gathering

is believed to cause storms and

lightning. In Zimbabwe, clearance has to

be obtained from ancestral spirits before

entering certain forests where Warburgia

salutaris occurs. In each of the above

cases (excepting Agapanthus umbellatus),

the species concerned are popular, scarce

and effective. These intentional

conservation practices may be due to the

century-old history of trade in these

plants in the southern African region.

Government legislation has played a

largely ineffective role in controlling

the use of medicinal plants in Africa.

Under colonial administration, religious

therapy systems practised by diviners

were equated with witchcraft and

legislated against almost everywhere

(Cunningham, 1990; Gerstner, 1938;

Staugard, 1985). In South Africa (and

possibly other parts of Africa) during

the colonial era, there were also

attempts to prohibit the sale of

traditional medicines within urban areas,

such as the efforts made by the Natal

Pharmaceutical Society in the 1930s in

Durban, South Africa. Apart from having

the temporary effect of driving informal

sector plant sellers and TMPs

underground, this kind of legislation has

been ineffective in reducing traditional

medicine use. Attempts to suppress

traditional medicine are not, however,

solely restricted to the colonial era: in

post-independence Mozambique, for

example, diviners involved in symbolic or

magico-medicinal aspects of traditional

medicine were sent to re-education camps

in an effort to do away with

“obscurantism” (Adjanohoun et

al., 1984).

Although forest legislation in most

African countries generally recognizes

the importance of customary usage rights

(including gathering of dead-wood for

fuel, felling poles and gathering latex,

gums, bark resins, honey and medicinal

plants) conservation land or certain

plant species are often set aside for

strict protection (Schmithusen, 1986). In

South Africa, for example, forestry

legislation was promulgated in 1914 for

the protection of economically important

timber species such as Ocotea bullata.

Specially protected status has been given

since 1974 to all species within the

families Liliaceae, Amaryllidaceae and

Orchidaceae due to their prominence in

the herbal medicine trade.

At best, this legislation has merely

slowed down the rate of harvesting.

Extensive exploitation within forest

reserves still occurs in South Africa.

One of the main reasons for this is that

legislation for core conservation areas

(CCAs) in the past has concentrated on a

“holding action” to maintain

the status quo and neglected to provide

local communities with viable

alternatives to collecting customary

plants.

Dynamics of the

commercial trade

If effective action is to be taken to

deal with the over-exploitation of

medicinal plants, there has to be a clear

understanding of the scale and complexity

of the problem.

Domestic

trade

Africa has the highest rate of

urbanization in the world, with urban

populations doubling every 14 years as

cities grow at 5.1% each year (Huntley et

al., 1989). In rural areas throughout

Africa, wild plant resources fulfill a

wide range of basic needs and are a

resource base harvested for informal

trade or barter, whereas in urban areas,

a much smaller range of species and uses

is found. In rural areas of the

Mozambique coastal plain for example, 76

edible wild plant species are used

(Cunningham, 1988a) but only five species

are sold in urban markets in Maputo.

Urbanization results in this general

reduction in the number of species and

the quantities of certain wild plant

resources used as people enter the cash

economy, and alternative foods, utensils

and building materials become available.

However, informal sector trade in two

categories of wild plant resources

continues to be very important in many

cities: fuelwood (alternative energy

sources such as electricity, gas and

paraffin are not available or affordable;

Eberhard, 1986; Farnsworth, 1988) and

medicinal plants.The range of

commercially sold medicinal species in

southern Africa remains wide despite

urbanization (over 400 indigenous species

in Natal, South Africa, for example;

Cunningham, 1990). Little attention has

been paid to the cultural, medical,

economic or ecological significance of

the herbal medicine trade, yet

traditional medicine sellers are a

feature of every African city (ECP/GR,

1983). Cities are concentrated centres of

demand drawing in traditional medicines

from outlying rural areas and across

national boundaries. Despite the

differences in volume and range of

species used, parallels can be drawn

between the trade in medicinal plants and

that in fuelwood:

(1) high proportions of people use

medicinal plants (70-80%) and

fuelwood (60-95%) (Leach and Mearns,

1988);

(2) high urban demand can

undermine the rural resource base by

causing the depletion of favoured but

slow growing species such as

Combretum (fuelwood, Botswana;

Kgathi, 1984) and Warburgia salutaris

(bark medicines, Zimbabwe);

(3) harvesting is a strenuous and

labour intensive activity with

financial returns, carried out by

rural people with a low level of

formal education and poor chance of

formal employment;

(4) supplies may be drawn from a

long distance away - from 200-500 km

for fuelwood in many African cities

(Leach and Mearns, 1989) and as far

as 800-1200 km for certain medicinal

plants in west Africa such as Entada

africana and Swartzia

madagascariensis or Synaptolepis

kirkii in southern Africa

(Cunningham, 1988a).

The herbal medicine trade is

characterized by two features. First,

from being almost solely an activity of

traditional specialists, medicinal plant

collection has now shifted to involve

commercial harvesters in the informal

sector, and (in South Africa at least)

formal sector traders (Table

2) who supply the large urban demand.

Women, rather than men, are increasingly

involved as non-specialist sellers of

traditional medicines, and this general

pattern is seen throughout Africa. In

rural areas and small villages, male and

female TMPs practise from their homes. In

larger villages, herbalists (mainly men)

dispense from a small quantity of

traditional medicines that they have

gathered themselves. In towns, larger

quantities of material are sold, some of

which are bought from commercial

harvesters, and in cities or large towns,

large quantities of plant material are

supplied by commercial harvesters and

sold through increasing numbers of

informal sector sellers (mainly women) to

urban herb traders or herbalists for

self-medication. Men drop out of

non-specialist sales as it becomes an

increasingly marginal activity, and only

persist as sellers of animal material.

Second, demand for traditional medicines

is highly species specific and

alternatives are not easily provided due

to the characteristics of the plant or

animal material, their symbolism, or the

form in which they are taken. These large

urban areas dictate prices, which are

kept low because of rising unemployment,

over-supply and cheap labour. Thus

nothing is paid towards the replacement

of the wild stocks.

In the stressful environment which is

a feature of many urban areas in Africa,

it is not surprising that demand has

increased for traditional medicinal plant

and animal materials which are believed

to have symbolic or psychosomatic value.

Table

2.

Number of traditional

medicine sellers (this excludes

chewing stick sellers) and herb

trader shops in selected African

urban areas, small towns (#),

large towns (*) and cities

(capital letters) from counts

during 1989 and early 1990.

| COUNTRY |

CITY/TOWN |

MARKET-BASED

SELLERS |

HERB

TRADERS |

| SOUTH AFRICA |

COTE D'IVOIRE

|

| ZIMBABWE |

| MOZAMBIQUE |

ZAMBIA

|

MALAWI

|

| SWAZILAND |

|

| DURBAN |

(3) |

ABIDJAN

Bouake* |

(4)

(1) |

| Harare* |

(2) |

| Maputo* |

(1) |

Lusaka*

Mongu# |

(2)

(1) |

Liiongwe*

Blantyre*

Zomba#

Mzuzu# |

(1)

(1)

(1)

(1) |

Mbabane*

Manzini# |

(1)

(1) |

|

| 392 |

22 |

270 |

111

64 |

4

26 |

107

37 |

| 36 |

25 |

11 |

| 25 |

19 |

6 |

16

3 |

5

3 |

11

0 |

3

8

3

2 |

3

8

3

2 |

0

0

0

0 |

3

4 |

2

2 |

1

2 |

|

| c.100 |

0

0 |

| 0 |

| 0 |

0

0 |

0

0

0

0 |

0

0 |

|

|

Traditional plant or animal

materials which bring luck in finding

employment, which guard against jealousy

(such as that engendered when one person

has a job whilst their peer group are

unemployed), or love-charms and

aphrodisiacs to keep a wife or girlfriend

are popular. Thus, employment options for

TMPs have increased with the stresses of

urban life. In addition, western-type

medical facilities have not been able to

cope with the rapidly growing urban

population. In Lagos, Nigeria, for

example, the ratio of medical doctors to

total population was 1 : 5000 in 1975

compared with 1 : 2000 in 1955 (Udo,

1982).

Traditional medical practitioners are

therefore attracted to urban centres

where employment benefits can be good, as

shown in studies in Nairobi (Kenya), Dar

es Salaam (Tanzania), Kampala (Uganda),

Kinshasha (Zaire) and Lusaka (Zambia)

(Good and Kimani, 1980) (Table 1).

In Zimbabwe there is a higher ratio of

TMPs to total population in urban areas

(1 : 234) than in rural areas (1 : 956)

(Gelfand et al., 1985). This is not

always the situation, however: in the

Kilungu district of Kenya, the ratio of

rural TMPs to people averaged 1 : 224,

while in urban Mathare, the overall ratio

was 1 : 883 (Good, 1987).

Box

1: Case study: The trade in chewing

sticks

Dentists are scarce in many parts of

Africa, particularly in rural areas. The

ratio of dentists: total population in

Ghana was 1 : 150 000 (compared to 1 : 3

000 in Great Britain) (Adu-Tutu et al.,

1979). Although diet plays a major role

in causing dental caries, the practice of

dental hygiene is also important. While

toothpaste and toothbrushes are widely

used by the sector of the population with

a high level of formal education,

toothpaste consumption is still low (e.g.

Adu-Tutu et al., 1979 in Ghana) and

chewing sticks are still in common use in

many parts of Africa, particularly west

Africa. Even when people would prefer to

use toothbrushes, they do not have access

to toothpaste due to high cost or

remoteness. Continued access to popular

and effective sources of chewing sticks,

which have anti-bacterial properties, is

important as a primary health care

measure.

While many hundreds of medicinal plant

species are used within a region, a

smaller number of the most popular

species accounts for much of the

commercial trade to urban areas. This

applies equally to chewing sticks. In

Mozambique for example, Euclea divinorum

and Euclea natalensis (Ebenaceae) are the

most commonly sold species, although

other species are used countrywide. In

Côte d’Ivoire, the most popular

sources of chewing sticks are Garcinia

afzelii and Garcinia kola and less

commonly used chewing sticks were

Zanthoxylum macrophyllum, Maytenus

senegalensis, Pycnanthus angolensis and

Enantia polycarpa. In Cameroon, only

Garcinia mannii and Randia acuminata were

the basis of a chewing stick

“cottage industry” (Staugard,

1985). Similarly, in southern Ghana, from

a sample of 880 people interviewed, six

species (distinguished by four local

names) accounted for 86% of all usage and

the majority of the commercial sales. The

majority of all these respondents depend

on bought material rather than collecting

it themselves, irrespective of size of

settlement they live in or their

educational status (Figure 2). The

species used were: nsokodua (Garcinia

afzelii and G. epunctata (51.1%; 597

people); tweapea (Garcinia kola (18.7%;

218); sawe (Acacia kamerunensis and

Acacia pentagona (9.2%; 108); and

owebiribiri (Teclea verdoorninana (6.7%;

77).

Figure 2.

A.

Acquisition of usual chewing

stick by buying (shaded columns)

and collecting (open columns)

among people of various sizes of

settlement (after Cunningham,

1988a)

B. Acquisition of usual chewing

stick by buying (shaded columns)

and collecting (open columns)

among people differing in

educational background (after

Adu-Tutuet al. , 1979).

|

International

trade

The herbal medicine trade is booming

business worldwide. In India, for

example, there are 46 000 licensed

pharmacies manufacturing traditional

remedies, 80% of which come from plants

(Alok, 1991). Another example is Hong

Kong, which is claimed to be the largest

market in the world, importing over US$

190 million annually (Kong, 1982). In

Durban (South Africa), in 1929 there were

only two herbal traders; by 1987, there

were over 70 herbal trader shops

registered. The species specific nature

of the demand for medicinal plants is

responsible for generating long distance

trade across international boundaries.

According to Malla (1982), 60-70% of the

medicinal herbs collected in Nepal are

exported to India, with 85-200 tons

exported annually between 1972 and 1980.

Similarly the Hong Kong market imports

Aquilaria heart-wood for incense

manufacture from rain forest in Thailand

and Malaysia. This is devastating

Aquilaria populations in core

conservation areas such as Khao Yai

National Park, Thailand (Cunningham,

pers. obs.; Cunningham, 1988a;

Cunningham, 1988b). Africa is no

exception to this pattern and an informal

sector trade in medicinal plants spans

long distances:

(1) the roots of Swartzia

madagascariensis and Entada africana

are traded 500-800 kms from Burkina

Faso and Mali to Abidjan, Côte

d’Ivoire;

(2) the roots of Synaptolepis

kirkii are traded 1200 km from the

southern border of Mozambique and

South Africa, via Johannesburg, to

Maseru (Lesotho);

(3) the bark of Warburgia

salutaris is traded from Swaziland to

Johannesburg (South Africa) and

Namaacha (on the Swaziland/Mozambique

border) to Maputo (Mozambique);

(4) the roots of Alepidea

amatymbica and bark of Warburgia

salutaris are traded from the Eastern

Highlands (Zimbabwe) to urban centres

in the west of the country such as

Bulawayo;

(5) mail-order trade in

traditional medicines is common in

South Africa (Figure 3).

|

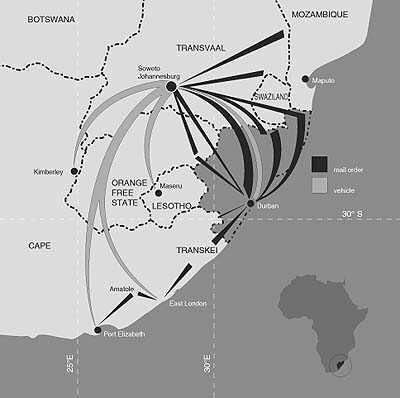

| Figure

3. Long

distance trade in Natal province,

South Africa, from the remotest

rural areas to major urban

centres through formal and

informal trade networks,

including mail order sales. |

An average of 25% of

prescription drugs sold in the USA during

the period 1959-1973 contained active

principles extracted from higher plants

(Farnsworth and Soejarto, 1985). Many of

these are derived from the same source as

those used in traditional medicine. On a

global scale, 74% of these chemicals have

similar or related uses in traditional

medicine (Farnsworth, 1988). Similarly,

many African plant species are the source

of a number of active ingredients for the

export market (Table 3, Photo 2). Because

of the low price demanded by plant

traders, even when technology for

chemical synthesis is available, it can

be cheaper for pharmaceutical companies

to continue to extract the active

ingredients from plants. In the

mid-1970s, for example, synthesis of

reserpine cost $1.25 g-1, compared to a

cost of $0.75 per g-1 for commercial

extraction from Rauvolfia vomitoria roots

(Oldfield, 1984).

Table

3. Indigenous

plants that are harvested as a

source of active ingredients for

export purposes, indicating what

part of the plant is harvested

for extraction of active

ingredients and whether the

plants are used in traditional

medicine or not.

| |

|

|

|

|

| SPECIES |

PART

USED |

INGREDIENT |

SOURCE

AREA |

TM |

| Adhatoda robusta |

? |

? |

Ghana (1) |

- |

| Allanblackia

floribunda |

fruit |

fat** |

Cote d'ivoire

(2) |

* |

| Ancistrocladus

abbreviatus |

? |

? |

Ghana (1) |

- |

| Corynanthe

pachyceras |

? |

corynanthine |

Ghana (1) |

* |

| |

|

corynathidine |

|

|

| |

|

yohimbine |

|

|

| Dennetia

tripetala |

? |

? |

Ghana (1) |

- |

| Duparquetia

orchidacea |

? |

? |

Ghana (1) |

* |

| Griffonia

simplicifolia |

seed |

BS11 lectin |

Côte d’

Ivoire,

Cameroon &

Ghana (1,2,5) |

* |

| Harpagophytum

procumbens |

root |

glucoiridoids |

Namibia (3) |

* |

| Harpagophytem

zeyheri |

root |

glucoiridoids |

Namibia (3) |

* |

| Hunteria eburnea |

bark |

eburine and

other alkaloids |

Ghana (1) |

* |

| Jateoriza

palmata |

root |

palmatrin |

Tanzania (4) |

* |

| |

|

jateorhizine

colambamine |

|

|

| Pausinystalia

johimbe |

bark |

yohimbine |

Cameroon (5) |

* |

| Pentadesma

butryacea |

fruit |

fat** |

Côte

d’Ivoire (2) |

* |

| Physostigma

venenosum |

fruit |

physostigmine |

Côte

d’Ivoire (2) |

* |

| |

|

(eserine) |

Ghana (1) |

* |

| Prunus africana |

bark |

sterols |

Cameroon, Kenya |

* |

| |

|

triterpenes

n - docosanol |

Madagascar (6)

|

* |

| Rauvolfia

vomitoria |

root |

reserpine |

Zaire, Rwanda, |

* |

| |

|

yohimbine etc. |

Mozambique |

|

| Strophanthus

spp. |

fruit |

ouabain |

West Africa |

* |

| Voacanga

africana |

seed |

voacamine |

Côte

d’Ivoire, |

* |

| |

|

|

Cameroon,

Ghana (1,2,5) |

|

| Voacanga

thouarsii |

seed |

voacamine |

Cameroon(1,2,5) |

* |

Note

:

Fat from Allanblackia stuhlmannii

fruits,used in soap making and

cosmetics industry (Lovett,

1988). Use of products from

Jateorhiza now limited mainly to

veterinary medicine (Oatley,

1979).References: 1 = (Abbiw,

1990); 2 = L. Ake Assi, pers.

comm.; 3 = (Nott, 1986); 4 = J.

Seyani, pers. comm.; 5 = (FAO,

1986); 6=(Catalano et al., 1985)

|

According to the

UNCTADD/GATT International Trade Centre,

the total value of imports of medicinal

plants for OECD countries, Japan and the

USA increased from US$ 335 million in

1976 to US$ 551 million in 1980 (Husain,

1991). Of the 200 tons of Harpagophytum

procumbens and H. zeyheri tubers exported

annually from Namibia, Germany imported

80.4%, with the remaining 12.8% sold to

France, 1.9% to Italy, 1.5% to USA, 1% to

Belgium and 1.2% sold locally or to South

Africa (Nott, 1986). Unfortunately, the

low prices paid for the plants do not

cover replacement or resource management

costs, and as such, major importers

demanding high volumes of plant material

are contributing to the decline of

medicinal plant species in Africa.

|

| Photo

2.

Medicinal plant seller at a

market in Abidjan, Côte

d’Ivoire, showing the

dominance of fresh leaf material

as a source of herbal medicines. |

|