Bwindi

Impenetrable Forest:

conservation importance and vegetation

change

Conservation

importance

The importance of

conserving Bwindi and other forests in

western Uganda has been explained by

Butynski (1984) and Struhsaker (1987).

Detailed comment here is limited to

aspects relating to forest plants.

|

| Photo

1.

An unidentified Memecylon

(Melastomataceae)

species. |

|

Although

tree species diversity of Bwindi

Impenetrable Forest is low

compared with high diversity rain

forest, it is important not only

as a representative of the

Afromontane centre of endemism

for plants (Photo 1), but also

for animals restricted to this

habitat (Butynski, 1984; Howard,

1991) (Tables 1 and 2). A 1ha

plot surveyed for trees >10 cm

dbh (diameter at breast height)

in Amazonian rain forest in Peru,

for example, contained 275

species, representing 50 families

(Peters et al., 1989), compared

to only 45-50 tree species >10

cm dbh in 1 ha of Bwindi

Impenetrable Forest at 2000-2200

m asl, and only 20 tree species

per ha in forest at 2400 m asl

(Howard, 1991). Bwindi

Impenetrable Forest contains tree

genera endemic to Afromontane

forest, and many tree species

that typify Afromontane rain

forest are also represented.

|

Although Lovoa

swynnertonii (Meliaceae) is the only tree

species listed as endangered, Bwindi

Forest contains a number of tree species

not found elsewhere in Uganda, or

represented in Uganda only in

Kabale-Rukungiri.

|

| Photo

2.

Fruit of Allanblackia

kimbiliensis

(Clusiaceae). |

|

(Although

Allanblackia kimbiliensis (Photo

2), Brazzeia longipedicellata,

Grewia mildbraedii,

Strombosiopsis tetrandra,

Maesobotrya floribunda (plus

Chrysophyllum pruniforme, which

Howard (1991) has since recorded

from Budongo and Itwara forests)

were thought to be confined to

Ishasha Gorge (Hamilton, 1991),

this is collecting surveys.

Allanblackia probably an artefact

of previous plant |

Bwindi Forest is a

Pleistocene refugium containing not only

plants typical of Afromontane forest but

also representatives of the

Guineo-Congolian flora, such as the

secondary forest tree Musanga leo-errerae

(Cecropiaceaea), the shrub Agelaea

pentagyna (Connaraceae), herbs such as

Ataenidia and Marantochloa (Marantaceae)

and parasitic plants such as Thonningia

sanguinea (Balanophoraceae).

Table

1. The seven centres of

endemism in Africa, with

numbers of seed plants,

mammals (ungulates and

diurnal primates) and

passerine bird species in

each, and the percentage

of these endemic to each

unit (in Huntley, 1988).

|

Biogeographic

Unit

|

Area

(1000 km2)

|

Plants

|

Mammals

|

Birds

|

|

| |

|

No.of

spesies

|

%

endemic

|

No.of

spesies

|

%

endemic

|

No.of

spesies

|

%

endemic

|

Guinea-Congolian

|

2815

|

8000

|

80

|

58

|

45

|

655

|

36

|

Zambesian

|

3939

|

8500

|

54

|

55

|

4

|

650

|

15

|

Sudanian

|

3565

|

2750

|

33

|

46

|

2

|

319

|

8

|

Somaii-Masai

|

1990

|

2500

|

50

|

59

|

14

|

345

|

32

|

Cape

|

90

|

8500

|

80

|

14

|

0

|

187

|

4

|

Karoo-Namib

|

692

|

3500

|

50

|

13

|

0

|

112

|

9

|

Afromonte

|

647

|

3000

|

75

|

50

|

4

|

220

|

6

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bwindi Forest is a major

catchment area and a source of water to

surrounding rural communities, and

through Lakes Edward and Mutanda via the

Nile to the Mediterranean. It can also

provide economic benefit from

non-consumptive uses of the forest (e.g.

eco-tourism) and consumptivuses.

Consumptive uses may be of resources

meeting basic needs of the surrounding

community (e.g. plant resources) or on a

wider scale (e.g. genetic values of wild

relatives of crop and forage plants, and

chemical structures for new

pharmaceuticals).

Table 2. Tree

species in Bwindi forest with

particular conservation

importance.

|

Tree genera in

Bwindi endemic to Afromontane

forest

Afrocrania

(Cornaceae);

Hagenia (Rosaceae);

Ficalhoa, Balthasaria (Theaceae)

and Xymalos (Monimiaceae).

|

Tree species in

Bwindi that typify Afromontane

forest

Entandrophragma

excelsum (Meliaceae); Myrianthus

holstii (Cecropiaceae);

Podocarpus latifolius

(Podocarpaceae); Ocotea

usambarensis (Lauraceae); Agauria

salicifolia (Ericaeae); Aningeria

adolfi-friedericii, Chrysophyllum

gorungosanum (Sapotaceae); Hallea

(=Mitragyna) rubrostipulata

(Rubiaceae); Parinari excelsa

(Chrysobalanaceae); Prunus

africana (Rosaceae); Syzygium

guineense (Myrtaceae) and

Strombosia scheffleri

(Olacaceae).

|

Tree species in

Bwindi not found elsewhere in

Uganda (Butynski, 1984; Howard

1991)

Allanblackia

kimbiliensis (Clusiaceae);

Brazzeia longipedicellata

(Scytopetalaceae); Grewia

mildbraedii (Tiliaceae);

Strombosiopsis tetrandra

(Olacaceae); Maesobotrya

floribunda (Euphorbiaceae);

Xylopia staudtii (Annonaceae),

Balthasiaria (=Melchiora)

schliebenii (Theaceae), Guarea

(=Leplaea) mayombensis

(Meliaceae) and an unidentified

Memecylon species (Melastomaceae)

which occurs on alluvial terraces

in the Nteko and Buhoma areas.

|

Tree species

found elsewhere in Africa but

restricted in Uganda to the

south-west (Butynski, 1984;

Howard 1991)

Cassipourea

congoensis (Rhizophoraceae);

Chrysophyllum pruniforme

(Sapotaceae); Drypetes

bipindensis and Sapium

leonardii-crispi (Euphorbiaceae);

Oncoba routledgei and Dasylepis

racemosa (Flacourticeae);

Tabernaemontana odoratissima

(Apocynaceae); Cola bracteata

(Sterculiaceae); Pauridiantha

callicarpoides (Rubiaceae);

Pittosporum spathicalyx

(Pittosporaceae); Millettia

psilopetala (Fabaceae);

Dichaetanthera corymbosa

(Melastomataceae); Musanga

leo-errerae and Myrianthus

holstii (Cecropiaceae); Ocotea

usambarensis (Lauraceae);

Ficalhoa laurifolia (Theaceae).

|

To facilitate informed

decision-making, plant use and forest

conservation policy have to be seen

against the background influences of

climate and human disturbance of forest

ecosystems. Both have had a major

influence on African vegetation in the

past and will continue to do so in the

future, perhaps even more so with the

effects of global warming and human

population increase.

Climate

change

Massive oscillations in

the Pleistocene climate, caused by

expansions and shrinking of the polar

ice-caps, resulted in long, cool, dry

periods alternating with shorter, warmer,

moist periods. Equatorial forests, as

indicators of world climatic conditions,

are believed to have expanded outwards

from, or shrunk into, Pleistocene

refugia. Detailed pollen analysis from

cores taken in the Rukiga highlands near

to Bwindi Forest has provided evidence of

vegetation dynamics and climate change

over the past 40,000-50,000 years,

including forest expansion around 10,600

BP into the Ahakagyezi catchment along

the Ishasha river south-east of Bwindi

Forest (Taylor, 1990).

During the most recent

glacial phase (pre-12,000 BP), forests

were restricted to a few refugia, later

expanding outwards with moister, warmer

conditions (Hamilton, 1981). Hamilton

(1981) has stressed the importance of

conserving forests which retained forest

cover during the earlier arid phase.

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is considered

to be one of these refugia in Uganda. The

decline of forest tree species-richness

across Uganda from west to east is

considered to be indicative of this, and

forests in western Uganda, particularly

those of Bwindi-Kayonza and Bwamba are

thus considered to have the highest

national conservation priority (Hamilton,

1981; Howard, 1991).

People

and vegetation change

Dating of archaeological

remains from Matupi Cave in the eastern

Ituri Forest, Zaïre, indicates human

occupation 32,000-40,700 years ago (Van

Noten, 1977). Similar data for the Rukiga

highlands are not available, but it is

likely that, like the Mbuti

hunter-gatherers in the Ituri region,

Batwa Pygmy people originally occupied

the forests and savanna of south-west

Uganda and northern Rwanda.

From their study of Mbuti

hunter-gatherer subsistence in the Ituri

Forest, Hart and Hart (1986) suggest that

it is unlikely that hunter-gatherers

would have lived independently in the

forest interior, as for five months of

the year virtually no nutritionally

important wild edible plants are

available, honey is not abundant and,

although game meat is available, it has a

low fat content. From field observation,

the density and species abundance of

edible wild plants (the principal species

being Myrianthus holstii (fruits) and

Dioscorea spp. (ebikwa) tubers) appear to

be even lower than in the Zaïre lowland

forest studied by Hart and Hart (1986).

None of the Guineo- Congolian zone edible

fruit trees (e.g. Irvingia, Ricinodendron

heudelotii) that are major food sources

to Mbuti people occur in Bwindi Forest.

It appears likely therefore that Batwa

subsistence would have been dependent on

plant and animal resources of savanna and

wetlands, in addition to those of forest.

However, Batwa

hunter-gatherers may have manipulated

forest and savanna vegetation. Although

there is no direct evidence from the

Rukiga highlands on this, it may be that

Batwa hunter-gatherers achieved this

through the use of fire. Fire would have

been used seasonally in forest during

honey hunting and possibly in savanna to

attract game.

Fire could also have been

used as a tool in forest during dry

periods, to create disturbance and

stimulate production of Dioscorea tubers.

Dioscorea climbers are most commonly

found in secondary forest or forest

margins (Hart and Hart, 1986; this

study). Hunter-gatherers in southern

Africa, for example, use fire as a tool

to increase below-ground production of

edible Iridaceae corms (Deacon, 1983).

"Fire-stick farming" is also

thought to have been used by

hunter-gatherers in forests in New Guinea

for edible resources, including yams

(Dioscorea spp.) (Groube, 1989).

Dioscorea tubers are thought to have been

a major food resource of Mbuti Pygmy

peoples in the past (Tanno, 1981). In the

Ituri Forest, Mbuti Pygmy population

density was approximately 1 person per

km². The hunter-gatherer population

density in the Rukiga highlands in the

past is unknown, but was probably no

higher than this. It would be expected

therefore that with low human densities,

their impact on vegetation would have

been localized and subtle compared to the

clearing of forest by agriculturists.

Butynski (1984) estimated that the Batwa

Pygmy people accounted for less than 0.5%

of the total population. This would be

consistent with a population density of

(less than) 1 person per km² today.

|

| Photo

3.

Iron smelting technology

introduced into the

Rukiga highlands c. 2000

yr ago remains

essentially unchanged

today by blacksmiths

(omuhesi) in this area.

Wooden bellows (omuzuba),

made from Polyscias fulva

(omungo) wood and the

clay tuyère (encheru). |

|

Pollen

analysis has not only provided

evidence of shifting forest cover

in response to climate change

over the past 40,000-50,000

years, but also of the clearing

of forests in the Rukiga

highlands. Although previously

thought to have started before

about 4800 years ago (Hamilton et

al., 1989), a reassessment of

core material suggests that

clearing took place after about

2200 years ago (Taylor, 1990),

coinciding with the influx of

Bantu-speaking agriculturists

with iron-smelting technology

(Van Noten, 1979) (Photo 3).

Farming was probably based on

finger millet (Eleusine

coracana), sorghum (Sorghum sp.)

and possibly cow-peas (Vigna sp.)

and pigeon peas (Cajanus cajan)

which originate from the Horn of

Africa. Agriculture was

established in Rwanda (and

probably the Rukiga highlands) by

about 2000 years ago, resulting

in more permanent settlements and

concentrating the effects of

human occupation on the

surrounding vegetation due to

burning, clearing and cutting of

fuel (for iron-smelting (Photo 4)

and household use and other

purposes). |

This would also

have stimulated trade in forest products

(e.g. bush meat) for cultivated starches

between Batwa and Bakiga. Since then, a

wider range of crops has gradually been

introduced from Central and South America

(sweet potatoes, tomatoes, cassava,

pineapples, chilli peppers, groundnuts,

potatoes and tobacco), south-east Asia

(bananas, sugarcane), south-central China

and northern India (tea), the near East

(peas), Central Asia (carrots) and the

Mediterranean (cabbages). Agricultural

production occupies 83% of the population

of Uganda, accounts for nearly all export

earnings, and contributes 60% to GDP

(World Bank, 1986).

|

| Photo 4.

Polyscias fulva (omungo)

tree (Araliaceae)

favoured for wooden

bellows (omuzuba) used in

traditional iron-smelting

technology. |

|

In 1921, the

Ugandan population was 3 million

people (Howard, 1991), and by the

year 2000 it is projected to be

23.8 million (Bulatao et al.,

1990). At the same time, the area

of forest that formerly would

have been used for harvesting of

plant resources has rapidly

decreased, due to agricultural

clearing and burning. Harvesting

intensity therefore concentrates

on the remaining vegetation,

ultimately focusing on species

within core conservation areas. |

Extensive

transformation of the Rukiga highlands

landscape has occurred since the 1900s,

due to natural population increase and

migration from Rwanda, where population

density is 480 people per km² of arable

land (Balasubramanian and Egli, 1986).

Between 1948 and 1980, the population of

the Kabale and Rukungiri districts

increased by 90%, from 396,000 to 752,000

(Butynski, 1984). Today, the Rukiga

highlands are one of the most densely

populated areas of Uganda, with

population densities in the DTC area

surrounding the forest ranging from

102-320 persons per km² (Figure 2, page

5) (data from an unpublished DTC 1991

census). Intensive agriculture by a high

density of rural farmers has resulted in

removal of indigenous woody plants,

shorter and shorter fallow periods and a

reduction in species diversity. Situated

in one of the most densely populated

areas of Uganda, with a 115 km long

boundary surrounded by almost 100,000

people (Anon, 1992) Bwindi Impenetrable

National Park became an island in a sea

of rural farmers, gold-miners and

pit-sawyers (Photos 5-8).

|

|

|

|

| Photo 5. Bwindi

Forest, intact apart from

disturbance due to tree falls

(canopy gaps) and fire. |

|

|

Photo 6. The

impact of farming on forest:

fields in what was forest in

1950. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Photo 7.

Species-selective

over-exploitation and gap

formation: pitsawing. |

|

|

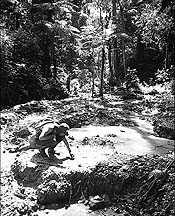

Photo 8. Disturbance

to river valley forest due to

illegal panning of alluvial gold. |

|