| Sustainable

use of wood products Although

the division in forestry terminology

between "minor" and

"major" forest products

reflects the bias of foresters managing

forests for timber, the slow growth rates

of forest hardwoods still makes

"major forest products" a

useful category, particularly where the

same species is used for different

purposes in different age classes.

As discussed above (page 13), forest

use differs greatly from the use of low

species diversity, highly productive

vegetation types such as Phragmites

wetlands or Cymbopogon thatch-grass,

where harvesting is seasonal and easy to

manage, with obvious clear cutting of

suitable stands.

Bwindi Forest is at the opposite end

of the scale. Instead of the 1-year

rotation applied in reed cutting

(Cunningham, 1985), sustainable

harvesting of forest for timber aims at a

rotation of 100 years (Leggatt and

Osmaston, 1961). Tree growth rates are

slow, so unlike reeds which regrow from

an underground rhizome within a year, the

time between final harvesting and

replacement of mature trees is seldom

less than 50 years, and often as much as

200 years (for oak trees in Europe for

example).

On the basis of growth measurements

from Afromontane tree species in southern

Africa, Stapleton (1955) considered that

under natural conditions, growth time to

marketable maturity for timber production

from Podocarpus latifolius was 230 years,

Ocotea bullata 220 years and Olea

laurifolia, 200 years.

Logging, particularly when mechanized,

affects mature forest, changing forest

structure and species composition,

resulting from canopy gap formation

(Howard, 1991). In addition to

differences caused by topography and soil

type, logging results in patchy

distribution of both species and size

class categories of trees and shrubs used

for bellows, building poles, beer boats

or bean stakes. It also influences the

availability of these resources, either

increasing the number of young saplings

(bean stakes, building poles) or

colonizing species in disturbed sites

(e.g. Polyscias fulva, Maesopsis eminii),

or decreasing stocks of large hardwoods

due to over-exploitation and competing

uses for timber.

Competing uses

This situation is complicated further

through competing uses for young trees or

saplings of the same species,

particularly as Bwindi Impenetrable

Forest is the most heavily pitsawn of all

principal forests in Uganda.

To foresters, whose objective is

hardwood timber production, saplings of

"reserved species" (Table 14,

page 41) represent regenerating timber

trees. To people from local rural

communities they also represent an

important source of beer boats (>50 cm

dbh), building material (5-15 cm dbh) or

bean poles (1.5-5 cm dbh), with high

density wood favoured due to greater

resistance to borer attack or fungal

infection.

| Table

14. Competing use of forest tree

and shrub species in successive

age/size classes for pitsawn

timber (>50 cm dbh), beer

boats (>50 cm dbh), building

poles (5 - 15 cm dbh) and bean

stakes (1.5 - 5 cm dbh) in Bwindi

forest. |

| Plant species |

Rukiga name |

Life form |

Pitsawn |

Beer boats |

Building poles |

Bean stakes |

| Alangium chinense |

omukofe |

tree |

*** |

|

* |

* |

| Albizia gummifera |

omushebeya |

tree (SF) |

|

|

* |

* |

| Alchornea hirtella |

ekizogwa |

shrub |

|

|

* |

*** |

| Arundinaria alpina |

omugano |

bamboo |

|

|

* |

*** |

| Baphiopsis parviflora

|

omunyashandu |

tree |

|

|

*** |

* |

| Beilschmiedia

ugandensis |

omuchoyo |

tree |

|

|

* |

|

| Bridelia micrantha |

omujimbu |

tree (SF) |

|

|

*** |

* |

| Carapa grandiflora |

omuruguya |

tree |

|

|

* |

* |

| Chrysophyllum

gorungosanum |

omushoyo |

tree (CP) |

*** |

|

* |

* |

| Croton megalocarpus |

omuvune |

tree (SF) |

|

|

* |

* |

| Cyathea manniana |

omungunza |

tree fern |

|

|

*** |

|

| Dichaetanthera

corymbosa |

ekinishwe |

tree |

|

|

* |

|

| Drypetes gerrardii |

omushabarara |

tree |

|

|

*** |

* |

| Drypetes gerrardii |

omushabarara |

tree |

|

|

*** |

* |

| Entandrophragma

excelsum |

omuyovi |

tree (CP) |

*** |

* |

* |

|

| Faurea saligna |

omulengere |

tree (SF) |

*** |

|

* |

|

| Ficalhoa laurifolia |

omuvumaga |

tree |

*** |

|

|

*** |

| Ficus sur |

omulehe |

tree |

|

*** |

|

|

| Ficus spp. (F. ovata,

etc.) |

ekyitoma |

tree |

|

*** |

|

|

| Galiniera saxifraga |

omulanyoni |

shrub |

|

|

* |

*** |

| Harungana

madagascariensis |

omunyananga |

tree (SF) |

|

|

*** |

* |

| Macaranga

kilimandscharica |

omurara |

tree |

|

|

* |

* |

| Maesa lanceolata |

omuhanga |

shrub |

|

|

*** |

* |

| Maesopsis eminii |

omuguruka |

tree (SF) |

*** |

|

*** |

|

| Markhamia lutea |

omusavu |

tree (SF) |

|

* |

*** |

* |

| Newtonia buchananii |

omutoyo |

tree (CP) |

*** |

*** |

* |

|

| Ocotea usambarensis |

omwiha |

tree (CP) |

*** |

|

*** |

* |

| Oxyanthus

subpunctatus |

? |

shrub |

|

|

|

*** |

| Parinari excelsa |

omushamba |

tree |

*** |

|

|

|

| Podocarpus latifolius

|

omufu |

tree |

*** |

|

* |

*** |

| Prunus africana |

omumba |

tree (CP) |

*** |

*** |

*** |

|

| Psychotria

schweinfurthii |

omutegashali |

shrub |

|

|

|

*** |

| Sapium ellipticum |

omushasha |

tree (CP) |

* |

*** |

* |

* |

| Strombosia scheffleri

|

omuhika |

tree (CP) |

*** |

|

*** |

* |

| Symphonia globulifera

|

omusisi |

tree (CP) |

*** |

|

* |

* |

| Syzygium guineense |

omugote |

tree |

|

|

*** |

|

| Tabernaemontana

holstii |

kinyamagozi |

tree (SF) |

|

*** |

|

|

| Tabernaemontana sp. |

kinyamate |

tree (SF) |

|

|

*** |

|

| Zanthoxylum gilletii |

omulemankobe |

tree (CP) |

*** |

|

* |

|

| indet. |

omukarati |

tree |

|

|

*** |

|

|

| Note: Canopy tree species are

marked (CP) and secondary forest

species (SF); *** high

preference, ** acceptable, * used

occasionally. |

For this reason,

despite their "reserved

status", hardwood trees such as

Newtonia buchananii (omutoyo) and Prunus

africana (omumba) are, and probably

always have been, favoured for beer

boats, and Ocotea usambarensis (omwiha)

for building poles.

Cutting of bean stakes is selective

for size rather than species, but if

saplings of canopy species fit into this

category, then they are cut (e.g. cutting

of Strombosia scheffleri (omuhika) and

Ocotea usambarensis (omwiha) in secondary

forest during this survey). Not only are

these species a useful resource to local

people, they also represent the future

forest canopy of the next century.

Trees with low density wood or small

shrubby species are not generally subject

to such competing uses, however. Examples

are:

- Low density timber species used

for beer boats but not for timber

or building poles (such as large

Ficus species such as Ficus sur

(omulehe) and F. ovata

(ekyitoma));

- Secondary forest colonizers

Polyscias fulva (omungo) and

occasionally Musanga leo- errerae

(omutunda) used for blacksmiths'

bellows but not for other uses

due to the soft wood.

- Bean poles cut from understorey

shrubs such as Psychotria

schweinfurthii (omutegashali),

but not for timber or beer boats,

and rarely for building poles.

Wood

requirements and supplies

In terms of supply and demand for

fuelwood and building poles, the

situation in the DTC area is similar to

that described by Howard (1991) for the

Bwamba and Bajonjo counties in western

Uganda, north-east of Bwindi Impenetrable

National Park. Population densities are

high, and land-holdings in intensively

cultivated landscape are similar - 0.2 ha

per person in the DTC area (Kanongo,

1991); 0.26 and 0.19 ha per person

respectively in Bwamba and Bakonjo

counties (Howard, 1991).

In Bwamba, Howard (1991) calculated

that the 121,600 people (17,000

households) would require about 151,000

m³ of fuelwood and 4600m³ building

poles every year (on the basis of a

fuelwood consumption rate of 1.24 m³ per

person per yr and a building pole

requirement of 0.27 m³ per household per

yr or 0.038 m³ per person per yr). The

DTC area is occupied by a similar number

of people (over 99,000 people, 19,000

households).

This situation has been worsened by

the rapid clearing and burning of

indigenous forest for agriculture outside

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. In

1954, approximately 120 km² of forest

remained in the DTC area within a 15 km

radius outside the Bwindi Forest

boundary. By 1972 this had been reduced

to 42 km² of forest, and by 1983, less

than 20 km² remained (Butynski, 1984).

Now, apart from forest patches in less

densely populated parishes such as Nteko,

virtually nothing remains.

Removal of forest outside of Bwindi

Impenetrable National Park has reduced

supplies not only of fuelwood and

building poles, as Howard (1991) points

out, but also of natural forest as a

source of bean stakes, which although

relatively small in diameter are needed

in vast quantity, and beer boats, which

although required in smaller numbers are

large trees, some of which are species

already over-exploited by pitsawyers

(Newtonia, Prunus) or which are

"keystone species" favoured by

frugivorous birds and primates (Ficus,

Prunus). Through this process, the

national park has become a focal point of

harvesting pressure.

Wood resources

availability

For beer boats large

trees are used (usually >50 cm dbh),

and most beer boats are greater than 40

cm in diameter (see Figure 4). Density of

large trees suitable for beer boats is

low in the multiple-use area, judging

from field observation, and a 1 ha plot

carried out in an Allanblackia - Syzygium

guineense dominated forest site selected

as representative of the forest. This had

a high number of beer boats per ha, due

to the flat terrain and absence of any

pitsawing activity there in the past.

Despite this, only 3 (2.6%) of the 114

trees >30 cm dbh (or 4.6% of the trees

>50 cm dbh) were suitable for beer

boats. With the exception of moist sites

with a high density of Ficus trees,

pitsawn sites would be expected to have

an even lower density of potential beer

boats. Growth rates of most tree species

favoured for beer boats are unknown for

this area. It is likely, however, that

Ficus sur and Ficus ovata would be

expected to reach the minimum tree

diameter (50 cm dbh) suitable for beer

boats in 20-30 yr, and Prunus africana or

Newtonia buchananii in 40-50 yr, both of

which greatly exceed the average

life-span of most beer boats (9 yr). With

improved road networks and urbanization,

marketing of banana beer, and therefore

demand for beer boats can be expected to

increase.

Building poles come

from trees intermediate in size between

those used for bean stakes and beer

boats. Resource assessments evaluating

trees within 20 x 20 m plots for

suitability for building purposes on the

basis of durability, diameter and

straightness, showed that there were

fewer building poles per ha (Figure 8)

than resource users anticipated from

visual assessments made before

quantitative work was done. Visual

assessments of resource availability made

with local people reported in Scott

(1992) therefore need to be considered

with caution.

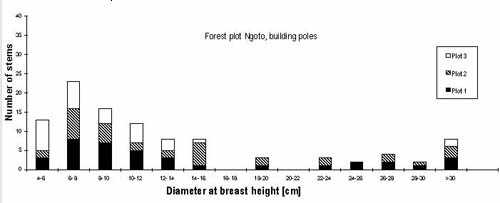

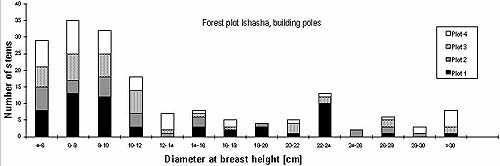

|

|

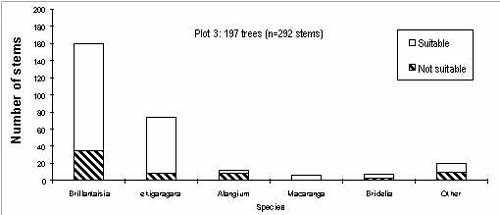

| Figure

8.

Combined number of tree stems in

2 cm size-class intervals for

four and three 20 x 20 m plots

(combined total of 0.28 ha) in

secondary forest in the Ishasha

gorge and Ngoto swamp areas

respectively, showing the number

of stems in the size-class range

preferred for building purposes

(5-15 cm dbh). |

| |

In the seven plots

surveyed, only 20.8% (8.3) poles per plot

were classed as very good for building

poles and 52.7% (21) poles per plot were

accepted (see Figure 5, page 35).

Although additional plots are required,

in the absence of other data this would

indicate an average density of 207 very

good poles per ha, or a total of 525

useable poles per ha.

Building pole cutting was not

widespread, and despite the big demand

for poles, high intensity harvesting was

limited to a few patches in secondary

forest. This is attributed to the

widespread cultivation of Eucalyptus and

black wattle, and the less

labour-intensive harvesting from these

cultivated tree species.

Counts in 20 x 20m plots in fields of

climbing beans in the Rubuguli and Nteko

areas during this survey showed that

there were 48,000-52,000 bean

stakes per ha of climbing beans.

By comparison, two forest plots in

Alchornea hirtella (ekizogwa) dominated

forest understorey favoured for bean

stakes (and the highest density of plots

sampled) (Figure 9, page 44), contained

479-630 per 20 x 20m plot, or

approximately 12,000-16,000 bean stakes

per ha, less than half as many as are

required for climbing bean cultivation.

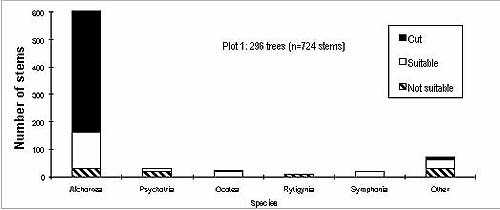

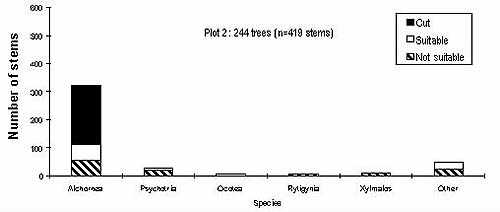

|

|

|

|

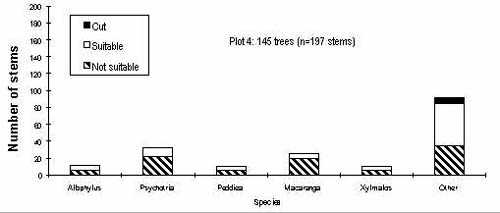

| Figure

9. Data

from four 20 x 20m plots in

secondary forest in the Rushaga

area, showing selectivity and

high proportion of stems cut for

bean stakes in Alchornea hirtella

(ekizogwa) dominated understorey

(Plots 1 and 2), and low degree

of harvesting in less favoured

sites (Plots 3 and 4). |

| |

Bean stakes last 2-3

seasons, and beans are a major crop in

the Rubuguli, Nteko, Rushaga, Nteko and

Nyamabale areas. Total demand for bean

stakes in the DTC must represent millions

of saplings per year.

Two additional points are significant

here. First, distribution of Alchornea

hirtella dominated stands is patchy, and

density of bean poles in the surrounding

areas is significantly lower (3000-6000

bean stakes per ha). Second, the

Alchornea hirtella patches are already

heavily utilized, with 58% (429) of stems

cut in the plot with the highest density

of bean stakes, and 35% (186) of stems

cut in the adjacent, lower density plot .

Cultivation of

wood resources

Shortages of fuelwood, building poles

and bean stakes are being experienced in

the DTC area, and a shortage of large

trees for beer boats can be expected in

the future. Reasons for wood scarcity,

and solutions to the problem are

recognized by local people.

Trees (particularly Eucalyptus) are

planted in the DTC area, mainly for

building poles, but are inadequate to

meet either the existing or the future

demand (Table 15, page 45). The need for

building poles was also the main reason

for tree planting in Bwamba, but it was

considered to provide only 328 m³ of the

total annual demand of the 151,000 m³ of

fuelwood, 4600 m³ of building poles and

annual increase in demand for timber of

5280 m³. It is likely that a similar

situation exists in the DTC project area.

| Table

15. Attitudes and approaches to

tree planting in the DTC area

(from data in Kanongo, 1990). |

| Reasons for

planting(n = 115) |

Species planted (n =

120) |

Source of seedlings

(n = 120) |

Species preferred for

building (n = 120) |

Planting site(n =

120) |

| Building (73) |

Eucalyptus (92) |

Own seedlings (89) |

Eucalyptus (106) |

Uncultivated land

(98) |

| Fuelwood (28) |

Acacia mearnsii (46) |

Forest dept. (33) |

Acacia mearnsii (59) |

House compound (49) |

| Sale (5) |

Cupressus (43) |

Community nursery

(13) |

Cupressus (14) |

Boundaries (47) |

| Other (9) |

Markhamia (5) |

Other (8) |

Markhamia (10) |

Among crops (34) |

| |

Sesbania (5) |

|

Other (9) |

In pasture (29) |

| |

Other (2) |

|

|

Fallow lands (19) |

| |

|

|

|

Other (roadsides) (4) |

|

Elephant grass

(Pennisetum purpureum) and trees

(particularly Eucalyptus) are also

planted for bean stakes, while Ficus

cuttings are planted for beer boats

(recorded in the Ngoto area) and canoes

(Lake Bunyonyi). In some areas, even

hardwood timber trees have been planted,

with Entandrophragma (omuyovi) reaching a

dbh of 90 cm within 40 years (Photos 21

and 22, page 45). Such local initiatives

need to be recognized and encouraged.

|

|

|

| Photo 21. Mr. K.

Byarugaba, second generation

Entandro-phragma (omuyovi)

planter with one of six 1 year

old trees at his homestead in the

Ngoto area . |

|

Photo 22.

Entandrophragma excelsum

(omuyovi) planted in 1950 at the

same homestead by the late father

of Mr. K. Byarugaba. |

| |

|

|

| Box

6. Recommendations for wood use *

Tree planting outside forest

reserves should be undertaken as

an urgent priority, as

recommended by Butynski (1984),

Hamilton (1984), Struhsaker

(1987) and Howard (1991). The

existing single line of Cupressus

that marks the boundary of Bwindi

Impenetrable National Park needs

to be paralleled by planting a

strip of fast-growing exotic or

indigenous trees useful both for

building purposes and fuelwood.

* Initiatives already taken by

local farmers in tree cultivation

need to be supported through

greater supply of seedlings and

the establishment of nurseries.

DTC staff are already involved

with an agroforestry programme.

In addition to work underway,

critical areas with high

population densities, little

woody cover and steep slopes need

to be identified and become a

priority, as short-term rotation

crop production on steep slopes

is unlikely to be sustainable due

to high soil losses.

* Cultivation of bamboo and

elephant grass (Pennisetum

purpureum) should be encouraged

as a soil conservation measure on

bunds and in water-courses, as

well as to provide building

material and bean stakes.

* Subject to further

investigation, wood carvers in

parishes within the DTC area

could be registered and involved

in a rotational management system

for carving of household utensils

(e.g. Rapanea melanophloeos for

carved walking sticks).

* Felling of Polyscias fulva

trees for making blacksmiths'

bellows should be permitted

within multiple-use zones.

* CARE/DTC-Uganda also need to

promote the cultivation of trees

suitable for grinding mortars and

carving (e.g. Markhamia lutea,

Rapanea melanophloeos), and

investigate the viability of

introducing appropriate

technology mills for millet and

groundnuts as an alternative to

hardwood mortars.

* No felling of trees for beer

boats, building poles or bean

stakes should be allowed in

multiple-use areas.

* Attention should be focused

on providing alternative sources

of fuelwood outside the forest,

recognizing that the use of

dead-wood from multiple-use zones

can only meet a fraction of local

needs, and that staff capacity

for multiple-use management is

limited.

*Involve community leaders

from Resistance Council (RC)-1

level (village level) upwards in

tree planting, inducing people to

plant a target number of trees

per year.

* Brick-makers, potters and

waragi makers should be

encouraged to plant a greater

number of trees to balance the

higher fuel consumption rates of

these activities.

* Forest destroyed by arson

should be closed to any

utilization for fuelwood or

building poles. Both fallen and

standing trees play an important

role in preventing soil loss on

steep slopes and also in trapping

seeds, as well as providing

perches for birds dispersing seed

into disturbed sites. The use of

wood for fuel could also provide

an incentive to burn the forest

more regularly if wood shortages

increase, instead of planting

trees as an alternative supply.

* Recommendations for

additions of land adjacent to the

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park

should be followed through as

soon as possible, even if zoned

as part of multiple-use areas.

Critical sites are the Kitahurira

corridor, which needs to be

widened through becoming the

focus of tree planting activity

and Ngoto Swamp, where a strip of

land at least 50 m wide around

the swamp needs to be negotiated

for tree planting. All uses of

plants from the Cyperus papyrus

(efundjo) swamp should be allowed

to continue. Ficus trees should

be planted around the swamp from

cuttings as a source of beer

boats in the future.

* Although exotic tree species

are commonly planted and are

extremely useful, some indigenous

species also have potential for

fulfilling local needs, and are

worth considering. Maesopsis

eminii, Harungana

madagascariensis, Maesa

lanceolata, Dodonaea viscosa,

Trema orientalis, Millettia dura

and M. lutea for example, all

grow well in disturbed sites,

have many uses (such as building)

and are suited to local

conditions. The exceptional

coppicing ability of Alchornea

hirtella makes it a good

candidate for managed coppice

rotations in private woodlots.

|

|