| The impact of the

trade in medicinal plants Commercial

gathering of traditional medicines in

large countries with small urban

populations (e.g. Mozambique, Zaire and

Zambia) is limited and cases of

over-exploitation are rare. Harvesting by

TMPs continues usually to be selective

and on a small scale, and traditional

conservation practices, where they exist,

would be expected to be retained. In

African countries with high rural

population densities and small cities

(e.g. Rwanda), gathering is also expected

to be small scale, and where a species is

popular and supplies are low due to

habitat destruction and agricultural

expansion, the tree will suffer a

“death of a thousand cuts”

rather than one-off ring-barking due to

commercial harvesting (see Photo 3).

The emergence of commercial medicinal

plant gatherers in response to urban

demand for medicines and rural

unemployment has resulted in indigenous

medicinal plants being considered as an

open access or common property resource

instead of a resource only used by

specialists. The resultant commercial,

large-scale harvesting has been the most

significant change, although seasonal and

gender related restrictions have also

altered. Rural traditional medical

practitioners and the hereditary chiefs

who traditionally regulate resource

management practices admit that

ring-barking and over-exploitation by

commercial gatherers are bad practices

that undermine the local resource base.

In Natal (South Africa) it appears that

restrictions placed by traditional

community leaders and enforced by headmen

and traditional community policemen have

reduced commercial exploitation of local

traditional medicinal plant resources.

With cultural change, increased entry

into the cash economy and rising

unemployment however, these controls are

breaking down.

Ring-barking or uprooting of plants is

the commonest method of collection used

by commercial gatherers (Photo 6). Where

urban populations (and resultant

commercial trade in traditional

medicines) are relatively small, but high

rural population densities and an

agricultural economy have cleared most

natural vegetation, tree species such as

Erythrina abyssinica and Cassia

abbreviata, which are popular and

accessible, have small pieces of bark

removed (Photos 3 and 4), rather than a

one-off removal of trunk bark (Photos 5

and 6).

Photos 3 to

6. Declining rural resource base

under non-commercial demand, but

limited supplies

|

|

|

|

| (3)

Erythrina abyssinica (Fabaceae),

Malawi (“death from a

thousand cuts”) and |

|

(4)

Cassia abbreviata (Fabaceae),

Zimbabwe, |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| (5)

Large pieces of Warburgia

salutaris (Canellaceae) bark from

Namaacha on the Swaziland border

commercially gathered for sale in

Maputo, Mozambique, |

|

(6)

Curtisia dentata (Cornaceae) tree

in Afro-montane forest, South

Africa, debarked for sale in

Durban, a city 100 km away. |

In South Africa, where

the taboo against gathering of

traditional medicines by menstruating

women was widespread in the past, urban

herbalists now no longer place importance

on this when buying plants from urban

markets, or in some cases, treat the

plants to magically “restore their

power”. Strict seasonal restrictions

are still placed on the gathering of

Siphonochilus aethiopicus rhizomes in

South Africa and Swaziland, but

commercial collection of Alepidea

amatymbica rhizomes now takes place

“on misty days” in summer

(although harvested material is stored

away from the homestead for fear of

lightning). Even where seasonal

restrictions are still in place, demand

can exceed supply. Siphonochilus

natalensis for example, had disappeared

from its only known locality in Natal

before 1911 as a result of trade between

Lesotho and Natal (South Africa)

(Medley-Wood and Evans, 1898).

It is clear that medicinal plant

species gathered for commercial purposes

represent the most popular and often most

effective (physiologically or

psychosomatically) herbal remedies. From

historical records (Gerstner, 1938, 1939;

Medley-Wood, 1896) it is clear that the

majority of species that were popular in

the past are still popular today.

Examples in southern Africa include

Erythrophleum lasianthum, Cassine

transvaalensis, Alepidia amatymbica and

Warburgia salutaris. Commercially sold

species thus represent a “short

list” of the medicinal plants used

nationally, since many species that are

used to a limited extent in rural areas

are not in demand in the urban areas.

Also important from a resource management

point of view, is that in virtually all

African countries, it is not the limited,

selective harvesting by specialist TMPs

that represents the problem. In most

cases, non-sustainable use of favoured

species results from commercial

harvesting to supply an urban demand for

traditional medicines, after clearing for

agricultural or urban associated

development has already taken place. The

widespread commercial harvesting and sale

of the same genera and species throughout

their distribution range is significant

(e.g. Solanum fruits, Erythrophleum bark,

Abrus precatorius seeds, Myrothamnus

flabellifolius stems and leaves and

Swartzia madagascariensis roots)

(Appendix 1).

Medicinal plant gatherers are familiar

with which species are becoming difficult

to find, either because of limited

geographical distribution, habitat

destruction or over-exploitation. Their

insights, coupled with botanical and

ecological knowledge of the plant species

involved, provide an essential source of

information for a survey of this type. In

this survey, it was not considered

constructive to distinguish between plant

species with symbolic uses and those with

active ingredients. The important

question here is whether the species are

threatened or not, because:

(1) species that have a purely

symbolic value are nevertheless important

ingredients of traditional medicines for

their psychosomatic value and are as

effective as placebos are in

urban-industrial society;

(2) the majority of traditional

medicines have not been adequately

screened for active ingredients and a

number of species, for example Rapanea

melanophloes in southern Africa, while

being primarily used for symbolic

purposes, also have active ingredients.

Conservation efforts must therefore be

directed at all species vulnerable to

over-exploitation.

For any resource, a relationship

exists between resource capital, resource

population size and sustainable rate of

harvest. Low stocks are likely to produce

small sustainable yields, particularly if

the target species is slow growing and

slow reproducing. Large stocks of species

with a high biomass production and short

time to reproductive maturity could be

expected to produce high sustainable

yields, particularly if competitive

interaction is reduced by

“thinning”. The impact of

gathering on the plant is also influenced

by factors such as the part of the plant

harvested and harvesting method.

Sustainable

supplies of traditional medicines

Demand for fast growing species with a

wide distribution, high natural

population density and high percentage

seed set can be met easily, particularly

where leaves, seeds, flowers or fruits

are used (Photo 7). The common sale and

use of medicinal plant leaves as a source

of medicine in Côte d’Ivoire and

possibly other parts of west Africa

(Photo 2) is therefore highly significant

as it differs markedly from the high

frequency of roots, bark or bulbs at

markets in the southern African region (Photo 7). Throughout

Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland,

Zambia, Zimbabwe, and particularly South

Africa, herbal material that is dried

(roots or bark), or has a long shelf-life

(bulbs, seeds and fruits) dominates

herbal medicine markets (see Appendix 1).

In contrast, six sellers in Abidjan,

Côte d’Ivoire, primarily sold leaf

material (20-41 spp.), followed by roots

(1-16 spp.), bark (0-8 spp) and whole

plants (0-3 spp.). This situation was

typical of the 111 traditional medicine

sellers in Abidjan, apart from those

bringing material from Burkina Faso and

Mali, who sell more root and bark

material. The situation with chewing

stick sellers in Côte d’Ivoire and

other parts of west Africa is somewhat

different however, as stems and roots are

the major plant parts used, with

consequent higher impact on favoured

species.

|

| Photo

7.

Medicinal plants for sale at a

marketin Bulawayo, Zimbabwe,

showing the dominance of bark and

root material as a source of

herbal medicines. |

Despite limited

information on the population biology of

medicinal plants, it is possible to

classify target plant species according

to demand, plant life-form, part used,

distribution and abundance (Cunningham,

1990). The large category of traditional

medicinal plants which are under no

threat at all are the cause of little

concern to TMPs or to conservation

biologists. For these species, demand

easily meets supply. From a conservation

viewpoint, on an Africa-wide scale, there

are two categories of medicinal plants

that are of concern:

(1) Slow growing species with a

limited distribution which are the

focus of commercial gathering where

demand exceeds supply. Harvesting

expands to areas progressively

further afield, where rising prices

for the target species are incentives

to collect. This results in the

species being endangered regionally

and causes widespread depletion of

the rural resource base of TMPs.

Examples of this include Warburgia

salutaris in east and southern Africa

and Siphonochilus aethiopicus in

Swaziland and South Africa. Endemic

species with a very localized

distribution are a particular

problem, for example:

(a) Ledebouria hypoxidoides,

which is endemic to the eastern

Cape region (South Africa).

Herbalists were observed removing

the last bulbs from the locality

near Grahamstown (F. Venter,

pers. comm.).

(b) Mystacidium millari, also

endemic to South Africa, which is

threatened due to harvesting and

commercial sale as a traditional

medicine in the nearby city of

Durban, South Africa (Cunningham,

1988a).

(2) Popular species which are not

endangered because they have a wide

distribution, but where habitat

change through commercial harvesting

is cause for concern. Trichilia

emetica and Albizia adianthifolia for

example, are not a high priority for

conservation in southern Africa,

although they are a popular source of

traditional medicines. What is of

concern however, is that ring-barking

in “conserved” forests is

causing canopy gaps and changing the

forest structure, which can lead to

an influx of invasive exotic species.

This is important for local habitat

conservation.

Both categories are of particular

concern in protected area management, as

core conservation areas will ultimately

come under pressure from harvesting for

favoured species if they are difficult to

obtain elsewhere.

Information on the quantities of

traditional medicines being harvested or

sold is sparse, whether for the local

trade in traditional medicines, or for

export and extraction of active

ingredients. Apart from placing the

quantities required from cultivation into

perspective, the information available is

of little relevance unless expressed in

terms of impact on the species concerned.

In South Africa, harvesting from wild

populations of certain species is on a

scale that gives cause for concern

amongst conservation organizations and

rural herbalists, and a listing of

priority species is available

(Cunningham, 1988a) (Box 2). The same

applies to some chewing stick species,

such as Garcinia afzelii in west Africa.

The only quantitative data on the volume

of plant material sold comes from Natal

(South Africa), where medicinal plants

are ordered by urban based herb traders

in standard-size maize bags (Table 4).

Table

4. The

quantities of the herbal

medicines sold annually in the

largest quantity (in standard 50

kg size maize bags) by 54 herb

traders in the Natal region,

South Africa. Although very

popular, Helichrysum

odoratissimum (Asteraceae) is

excluded here as it is sold in

large bales (Cunningham, 1990).

| |

|

|

|

| PLANT

NAME |

ZULU

NAME |

PART

USED |

QUANTITY |

| general term |

Lawu, -ubu |

|

1966 |

| general term |

Ntelezi, -i |

|

1924 |

| general term |

Khubhalo, -i |

|

1883 |

| general term |

Mbiza, -i |

|

1211 |

| Scilla

natalensis |

Guduza, -in |

bulb |

774 |

| Eucomis

autumnalis |

Mathunga, -u |

bulb |

581 |

| Alepidia

amatymbica |

Khathazo, -i |

root |

519 |

| Adenia gummifera |

Fulwa, -im |

stem |

459 |

| Albizia

adianthifolia |

Solo, -u |

bark |

424 |

| Cilvia miniata |

Mayime, -u |

bulb |

397* |

| Clivia nobilis |

Mayime, -u |

bulb |

397* |

| Pentanisia

prunelloides |

Cimamlilo, -i |

root (lt)# |

343 |

| Senecio

serratuloides |

Sukumbili, -in |

leaves/stem |

340 |

| Gunnera perpensa |

Gobho, -u |

root |

340 |

| Rapanea

melanophloeos |

Maphipha-khubalo,

-u |

bark |

327 |

| Dioscorea

sylvatica |

Ngwevu, -i |

whole plant |

326 |

| Warburgia

salutaris |

Bhaha, -isi |

bark |

315 |

| Bersama species* |

Diyaza, -un |

bark |

295 |

| unidentified

species |

Bhadlangu, -u |

root |

288 |

| Kalanchoe

crenata |

Mahogwe, -u |

leaves/stem |

284 |

| Boweia volubilis |

Gibisila, -i |

bulb |

257 |

| Trichilia

emetica (& T.

dregeana) |

Khuhulu, -um |

bark |

252 |

| Turbina

oblongata |

Bhoqo, -u |

root |

249 |

| Rhoicissus

tridentata |

Nwazi, isi |

root |

244 |

| Bulbine

latifolia |

Bhucu, -i |

bulb |

240 |

| Ocotea bullata |

Nukani, -u |

bark |

234 |

| Stangeria

eriopus |

Fingo, -im |

root (lt)# |

233 |

| Cryptocarya

species** |

Khondweni, -um |

bark |

228 |

| Anemone fanninii |

Manzemnyama, -a |

root |

227 |

| Eucomis sp. cf.

bicolor |

Mbola, -i |

bulb |

224 |

| Rhus

chirindensis |

Yazangoma-embomvu |

bark |

222 |

| Helinus

integrifolius |

Bhubhubhu, -u |

stem |

222 |

| Schotia

brachypetala |

Hluze, -i |

bark |

220 |

| Vernonia

neocorymbosa |

Hlunguhlungu,

-um |

leaves/stem |

216 |

| Dioscorea

dregeana |

Dakwa, -isi |

whole plant |

212 |

| Ornithogalum

longibracteatum |

Mababaza, -u |

bulb |

208 |

| Erythrophleum

lasianthum |

Khwangu, -um |

bark |

201 |

| Solanum

aculeastrum |

Tuma, -in |

fruit |

198 |

| Curtisia dentata |

Lahleni,-um |

bark |

197 |

*

Bersama species = B. tysoniana,

B. lucens, B. stayneri and B.

swynii

** Cryptocarya latifolia and C.

myrtifolia

# root (lt) = root (ligno-tuber)

|

Sustainability

of chewing stick harvesting

Chewing sticks are obtained from wild

populations of indigenous plants, apart

from the infrequent sale of exotic

species such as Azadirachta indica and

Citrus sinensis (Appendix 1). Garcinia

afzelii is considered to be threatened by

this trade (Ake Assi, 1988b;

Gautier-Beguin, pers. comm.). In Nigeria,

Okafor (1989) reports that Randia

acuminata chewing sticks are still

collected from primary and secondary

forest within 3 km of villages, but that

the distance is increasing, which

indicates that the resource is being

depleted. At a single depot, for example,

Okafor (1989) recorded that five

commercial chewing stick collectors

assembled 1144 bundles of chewing sticks,

made up of seven or eight split stems one

metre long per bundle. What is highly

significant from a resource management

viewpoint, and has not been taken into

account previously, is that whilst peeled

twigs are used as chewing sticks from

most species, split stems and roots are

the source of the commercially sold

chewing sticks. Among the 27 species used

in Ghana, for example, high impact

harvesting of stem wood or root material

from only seven species accounted for 88%

of chewing sticks used. The low impact

use of peeled twigs as chewing sticks

accounted for the other 12 % of sticks

used and for the remaining 20 species

(Ake Assi, 1988b). Impact on those source

species which are cut down or up-rooted

to supply urban demand is therefore high.

Supplying

international trade

Few data are available on the

quantities of raw material harvested for

the pharmaceutical trade, or the

environmental impact of harvesting. It is

clear however that large quantities of

material are collected from the wild and

that harvesting can be very destructive.

The same can apply to plant material

collected for screening purposes. Juma

(1989) offers the example of Maytenus

buchananii: 27.2 tons of plant material

were collected by the American National

Cancer Institute (NCI) from a

conservation area in the Shimba Hills

(Kenya), for screening purposes as a

potential treatment for pancreatic

cancer. When additional material was

required four years after the first

harvesting in 1972, regeneration was so

poor that collectors struggled to obtain

the additional material needed.

No studies are known to have been

carried out on the social or

environmental consequences of harvesting,

for example:

(1) the 75-80 t of Griffonia

simplicifolia seed exported each year to

Germany from Ghana (Abbiw, 1990);

(2) the medicinal plant material

exported from Cameroon to France

(Voacanga africana seed (575 tons);

Prunus africana bark (220 tonnes),

Pausinystalia johimbe bark (15 t) (United

Republic of Cameroon, 1989).

However, Ake-Assi (pers. comm.)

reports that commercial gatherers in

Côte d’Ivoire chop down Griffonia

simplicifolia vines and Voacanga africana

and Voacanga thouarsii trees in order to

obtain the fruits. Concern has been

expressed about a similar situation in

Indonesia, where Rifai and Kartawinata

(1991) point out that:

“Export of medicinal plants has

been going on for many years, and the

demand in the international market keeps

increasing. One big Swiss pharmaceutical

company, for example, has requested eight

tons of seeds of Voacanga grandifolia and

are willing to pay a high price. This

species is rare and has light seeds. To

satisfy the above request, all available

seeds in the forest will perhaps have to

be harvested, leaving nothing for

regeneration. Similarly, five tons of

rhizomes of a rare Curcuma (tema badur)

has been sought by a West German

pharmaceutical company, and 100 kg year-1

of pili cibotii (fine hairs of Cibotium

barometz) by a French firm. It can be

imagined how many plants of these species

will have to be destroyed should such

requests be satisfied.”

If the international companies

involved in this trade are to operate in

a responsible manner, then this situation

needs to change to one of commercial

cultivation and sustainable use.

The real price of

trade

The categories of medicinal plant

species that are most vulnerable to

over-exploitation can be identified by

combining the insights of herbal medicine

sellers with knowledge on plant biology

and distribution (Cunningham, 1990).

However, due to the number of species

involved and the limited information on

biomass, primary production and

demography of indigenous medicinal

plants, no detailed assessment of

sustainable off-take from natural

populations is possible. Even if these

data were available, their value would be

questionable due to the intensive

management inputs required for managing

sustainable use of vulnerable species in

cases where demand exceeds supply.

Unsustainably high levels of

exploitation are not a new problem,

although the problem has escalated in

regions with large urban areas and high

levels of urbanization since the 1960s.

Prior to 1898, local extermination of

Mondia whitei had been recorded in the

Durban area of South Africa due to

collection of its roots “which found

a ready sale in stores”. By 1900,

Siphonochilus natalensis (an endemic

species now considered synonymous with

Siphonochilus aethiopicus; Gibbs-Russell

et al., 1987) had disappeared from its

only known localities in the Inanda and

Umhloti valleys due to trade to Lesotho.

This occurred despite a traditional

seasonal restriction on harvesting this

species. By 1938, all that could be found

of Warburgia salutaris in Natal and

Zululand was “poor coppices, every

year cut right down to the bottom”

(Gerstner, 1938). Most botanical and

forestry records reflect the impact of

commercial collection of Ocotea bullata

bark due to the importance of this

species for timber. Oatley (1979) for

example, estimated that less than 1% of

450 trees examined in Afro-montane forest

in South Africa were undamaged, and in

the same region, Cooper (1979) estimated

that 95% of all Ocotea bullata trees had

been exploited for their bark, with 40%

ring-barked and dying. The situation

would appear to be similar in Kenya,

where Kokwaro (1991) records that some of

the largest Warburgia salutaris and Olea

welwitschii trees have been completely

ring-barked and have died. In Zimbabwe,

due to the high demand and limited

distribution of this species, the

situation is worse, and all that remains

of wild Warburgia salutaris populations

are a few coppice shoots (S. Mavi pers.

comm., 1990). In Côte d’Ivoire,

Garcinia afzelii is considered threatened

due to harvesting for the chewing stick

trade (Ake Assi, 1988b). Destructive

harvesting of Griffonia simplicifolia,

Voacanga thuoarsii and Voacanga africana

fruits for the international

pharmaceutical market is also of concern

(L. Ake-Assi, pers. comm., 1989). In

Sapoba Forest Reserve, Nigeria, despite

traditional restrictions on bark removal,

Hardie (1963) observed how the trunk of a

large Okoubaka aubrevillei tree (a very

rare species in west Africa) “was

much scarred where pieces of bark had

been removed”. There appears to be

nothing published on the current status

of this species. Botanical records are

also scanty for bulbous or herbaceous

species, where little remains to indicate

former occurrence after the plant has

been removed. It would therefore be

useful to carry out damage assessments

for species such as:

(1) Okoubaka aubrevillei, Garcinia

afzelii, G. epunctata, and G. kola in

Côte d’Ivoire , Ghana, and

Nigeria;

(2) Warburgia salutaris in Kenya,

Tanzania and Zimbabwe;

(3) assessments of the impact of

Prunus africana and Pausinystalia

johimbe bark harvesting in Cameroon

and Madagascar, and fruit harvesting

of Griffonia simplicifolia, Voacanga

thuoarsii and Voacanga africana for

the international pharmaceutical

market.

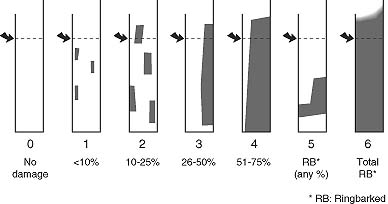

In South Africa, bark damage

assessments using a 7-point scale (Figure 4) were carried

out for key “indicator species”

(medicinal plants chosen for their

relatively slow growth rate - all were

trees), popularity as a source of

traditional medicines, their scarcity

(all were forest species, and indigenous

forest only covers 0.3% of South Africa),

and where bark removal took place.

|

| Figure

4. The

seven-point scale used in field

assessment of bark damage. All

assessments represent the degree

of bark removal below head height

(2 m), which is marked by the

dotted line and arrow in the

figure (Cunningham, 1988a). |

Bark damage assessments

confirmed most of the observations of

herbalists and herb traders (Tables 5 and 6), the exceptions

being species that were scarce not

because of over-exploitation, but due to

limited geographical distribution in the

region, such as Acacia xanthophloea and

Synaptolepis kirkii. They also

demonstrate the very different situation

to customary subsistence use, and this

fact needs to be taken into account in

legislation covering protected area

management where conservation of biotic

diversity is a primary objective.

Although the degree of bark damage

varies, the level at all sites where

commercial gathering is taking place is

high and concentrates on large diameter

size classes. What is significant is that

extensive damage has taken place in State

Forest, theoretically set aside for

maintenance of habitat and species

diversity (Figure 5).

In the eMalowe State Forest, Transkei,

South Africa, if coppice stems less than

2 cm diameter are excluded, then the

level of damage to Curtisia dentata and

Ocotea bullata trees encountered

represents 51% and 57% of trees having

more than half the trunk bark removed.

All Warburgia salutaris trees found

outside strict conservation areas in

Natal were ring-barked, and many of those

inside conserved areas had their bark

removed as well.

Table 5. The top

15 medicinal plant species

nominated as becoming scarce by

herb traders in South Africa (n =

44)

| |

|

|

|

| SPECIES |

ZULU

NAME |

PERCENTAGE |

No. of

traders |

| Warburgia

salutaris |

isibaha |

90 |

40 |

| Boweiea

volubilis |

igibisila |

84 |

37 |

| Siphonochilus

aethiopicus |

indungulo |

68 |

30 |

| Eucomis species |

umathunga |

64 |

28 |

| Ocotea bullata |

unukane |

61 |

27 |

| Hawarthia

limifolia |

umathithibala |

55 |

24 |

| Synaptolepis

kirkii |

uvuma-omhlophe |

52 |

23 |

| Scilla

natalensis |

inguduza |

36 |

16 |

| Eucomis species? |

imbola |

34 |

15 |

| Erythrophleum

lasianthum |

umkhwangu |

32 |

14 |

| ? |

uvumao bomvu |

32 |

14 |

| Curtisia dentata |

umlahleni |

27 |

12 |

| ? |

uphindemuva |

27 |

12 |

| Asclepias

cucullata |

udelenina |

27 |

12 |

| Cinnamomum

camphora |

uroselina |

25 |

11 |

| Begonia

homonymma |

idlula |

25 |

11 |

|

Table

6. The top

15 medicinal plant species

nominated as becoming scarce by

rural herbalists in South Africa

(n = 20)

| |

|

|

|

| SPECIES |

ZULU

NAME |

PERCENTAGE |

No.

of traders |

| Ocotea

bullata |

unukane |

90 |

18 |

| Warburgia

salutaris |

isibaha |

85 |

17 |

| Boweiea

volubilis |

igibisila |

70 |

14 |

| Scilla

natalensis |

inguduza |

65 |

13 |

| Helichrysum

species |

imphepho |

60 |

12 |

| Eucomis

species |

umathunga |

55 |

11 |

| Hawarthia

limifolia |

umathithibala |

55 |

11 |

| Cassine

transvaalensis |

ingwavuma |

55 |

11 |

| Alepidia

amatymbica |

ikhathazo |

50 |

10 |

| Pimpinella

caffra |

ibheka |

45 |

9 |

| Acacia

xanthophloea |

umkhanyakude |

45 |

9 |

| Curtisia

dentata |

umalhleni |

45 |

9 |

| Gunnera

purpensa |

ugobho |

45 |

9 |

| Cassine

papillosa |

usehlulamanye |

45 |

9 |

|

| Figure

5. Damage

to selected tree species in

“protected” forest

reserves where commercial bark

exploitation is taking

place:Ocotea bullata (Lauraceae)

and Curtisia dentata (Cornaceae)

in eMalowe Forest Reserve, South

Africa. (Cunningham, 1988a). Note

the selection for bark from large

trees. DBH = stem diameter at

breast height. |

| |

|

| |

|

Even fewer data are

available on the impact of harvesting

bulbs, roots or whole plants although

local depletion of Stangeria eriopus,

Gnidia kraussiana and Alepidea amatymbica

is known from Natal, South Africa.

According to C. Stirton (pers. comm.)

there has also been a marked reduction in

numbers of the Afro-montane forest

climber Dumasia villosa, which is sold in

large quantities in herbal medicine shops

(Cunningham, 1988a). C. Hines (pers.

comm.) has similarly recorded

exploitation of Protea gauguedi

populations to the point that, with the

possible exception of the eastern

Caprivi, the species could be considered

extinct in northern Namibia despite

attempts by the conservation department

to protect it. What is noteworthy in this

case is that it has taken place in

response to a local trade in an area

where urban centres are small. Commercial

harvesting of Harpagophytum procumbens

tubers in Botswana removed up to 66 % of

plants (Leloup, 1984). In Nambia,

however, this species was not considered

threatened as the 200 t exported each

year only represented 2% of total stocks

(de Bruine et al., 1977).

Increasing scarcity of popular species

is followed by a increased price, which

in turn results in greater incentives to

harvest remaining stocks. The effects of

this are firstly, decreased

self-sufficiency of traditional medical

practitioners as local sources of

favoured species decline, and secondly,

higher prices which people have to pay

for those species. As demand is a one of

the root causes of over-exploitation, the

most popular and effective species are

the most vulnerable.

The reasons

for concern

In spite of increasing urbanization, a

large proportion of the African

population has retained their reliance

upon this traditional approach to

healthcare and continue to consult TMPs

for medical treatment. Even where western

medicine is available, it is unlikely

that it will be adopted without first

establishing a framework for national

economic growth which would allow for

socio-economic and cultural changes to

take place, and give access to formal

education. Good (1987) writes:

“Although most countries in

Africa routinely allocate substantial

portions of their budgets to health

services and related infrastructure such

as water supplies, sanitary works and

roads, sustained improvements in

community health status and increased

accessibility to government and private

health services have not materialized.

Instead, health ministries find

themselves preoccupied just with

preventing the deterioration of existing

“aspirin and bandage”

services.”

In reality, most African countries are

experiencing an unprecedented economic

deterioration with per capita income

having fallen by an average of 0.4% since

1986, and Africa’s debt being

roughly three times greater than its

export revenue. The heavy reliance upon

traditional medicine therefore is

unlikely to change. At the same time,

there is significant evidence to show

that the supply of plants for traditional

medicine is failing to satisfy demand.

This problem has been exacerbated by

three main factors:

(1) A high rate of population

growth and urban expansion,

generating an informal and growing

species-specific trade network which

extends across international

boundaries.

(2) The change from medicinal

plant harvesting being a purely

specialist activity of TMPs, to one

involving an informal sector group of

commercial plant harvesters whose

prime motivation is profit. This is a

response to increased population and

greater demand and is resulting in a

disregard for traditional

conservation practice and a breakdown

of taboos and customs in the

opportunistic scramble for divining

supplies. High unemployment means

that labour is plentiful and cheap,

keeping prices low and sales high. In

the case of medicinal plants which

are harvested and exported for the

pharmaceutical industry, the price is

kept artificially low through price

agreements and does not reflect the

resource replacement costs.

(3) A decline in the total area of

natural vegetation as a source of

supply for medicinal plants has

occurred partly as a result of

competition for the land for other

uses such as forestry, agriculture,

fuel supply, etc., and partly due to

the commercial over-exploitation of

the medicinal plant themselves.

Examples where over-exploitation has

occurred include Monanthotaxis capea

which was formerly harvested for its

aromatic leaves and traded from Côte

d’Ivoire to Ghana. It is now

extinct in the wild after its last

remaining habitat in a forest reserve

was declassified and cleared for

agriculture. Pericopsis alata in

Côte d’Ivoire and Pericopsis

angolensis in Zambia and Malawi have

both been affected by timber logging

and Griffonia simplicifolia in west

Africa has been affected by

commercial harvesting for export for

the production of western

pharmaceuticals.

Focus of

management effort

The need in Africa for institution

building, and better staffing and funding

of herbaria, particularly in high

conservation priority areas is well known

(Davis et al., 1986; Hedberg and Hedberg,

1968; Kingdon, 1990; Leloup, 1984). There

is a great need for international

co-operation to conserve large regions of

high biotic diversity with small human

populations such as Guineo-Congolian

forest of the Zaire Basin. However,

medicinal plant resource management

problems exist not in these areas but in

densely populated and rapidly urbanizing

regions, and it is here that reaching a

balance between human needs and medicinal

plant resources is most urgent. This

involves:

(1) identification of habitat with

a high density of endemic families,

genera and species with medicinal

properties;

(2) pro-active management effort

around core conservation areas

through interaction with resource

users and provision of alternatives

to wild populations of threatened

species; this would include species

that are a high conservation priority

on a national scale. In the areas

visited, a preliminary listing is

given in Box 2.

Sites that are a conservation priority

from a more general species conservation

viewpoint may therefore not be a priority

with regard to conservation of

traditional medicinal plants. From

surveys of medicinal plant markets in

selected African countries for example,

it is clear that while the Cape Floral

region (which is of high conservation

priority due to the large number and

proportion of endemic species) is not

under threat from the herbal medicine

trade, but from habitat destruction.

From human demography data, we know

that the west and southern African

regions have highest rates of

urbanization. We also know that the

bigger the urban settlement, the larger

the traditional medicine markets (Table 2).

At a macro-scale, priority areas for

resource management action can be

determined through mapping overlay of the

main African phytochoria (Figure 6),

where information is known on numbers of

endemic plants, birds and mammals (Table 7) with the

major urban growth points (Figure 7). As

discussed previously, (Cunningham, 1990),

demand is most likely to exceed supply

for slow growing, slow reproducing

species with specific habitat

requirements (primarily forest trees).

Forests also contain a high number of

medicinal plant species, yet represent a

small (and declining) proportion of total

land area in the eastern section of

Africa and trees are often subject to

removal of bark or roots rather than

leaves for medicinal preparations (e.g.

Kenya, where forest reserves cover 2.7%;

Tanzania, 1-2%; South Africa, 0.3%;

(Cooper, 1985; Davis et al., 1986;

Kokwaro, 1991). The urgent challenge is

therefore to meet the increasing demand

from rapidly growing urban areas, restore

the self-sufficiency of TMPs affected by

this trade, and provide acceptable

alternative resources outside

increasingly fragmented core conservation

areas to stop over-exploitation of

favoured species inside them.

Table

7. The

seven centres of endemism in

Africa, with numbers of seed

plants, mammals (ungulates and

diurnal primates) and passerine

bird species in each, and the

percentage of these endemic to

each unit (after MacKinnon and

MacKinnon, in press)

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIOPGEOGRAHIC

UNIT |

AREA

(1,000 km square) |

PLANTS

No. of species |

%

endemic |

MAMMALS

No. of species |

%

endemic |

BIRDS

No. of species |

%

endemic |

| Guineo-Congolian |

2,815 |

8,000 |

80 |

58 |

48 |

655 |

36 |

| Zambesian |

3,939 |

8,500 |

54 |

55 |

4 |

650 |

15 |

| Sudanian |

3,565 |

2,750 |

33 |

46 |

2 |

319 |

8 |

| Somali-Masai |

1,990 |

2,500 |

50 |

50 |

14 |

345 |

32 |

| Cape |

90 |

8,500 |

80 |

14 |

0 |

187 |

4 |

| Karoo-Namib |

629 |

3,500 |

50 |

13 |

0 |

112 |

9 |

| Afro-montane |

647 |

3,000 |

75 |

50 |

4 |

220 |

65 |

|

| Figure 6. The

main African phytochoria (after

White, 1983) showing one high

conservation priority area (dark

grey) and

focal priority areas for action

on medicinal plant conservation (black). I. Guineo-Congolian

regional centre of endemism.

II. Zambezian regional centre of

endemism.

III. Sudanian regional centre of

endemism.

IV. Somalia-Masai regional centre

of endemism.

V. Cape regional centre of

endemism.

VI. Karoo-Namib regional centre

of endemism.

VII. Mediterranean regional

centre of endemism.

VIII. Afromontane

archipelago-like centre of

endemism (including IX,

Afroalpine archipelago-like

region of extreme floristic

impoverishment, not shown

separately).

X. Guinea-Congolia/Zambezia

regional transition zone.

XI. Guinea-Congolia/Sudania

regional transition zone.

XII. Lake Victoria regional

mosaic.

XIII. Zanzibar-Inhambane regional

mosaic.

XIV. Kalahari-Highveld regional

transition zone.

XV. Tongaland-Pondoland regional

mosaic

XVI. Sahel regional transition

zone.

XVII. Sahara regional transition

zone.

XVIII. Mediterranean/Sahara

regional transition zone.

|

|

| Figure 7.The

relative size and distribution of

major urban centres in

sub-Saharan Africa(after Udo,

1982). |

|

Box 2.

Preliminary listing of high

conservation priority traditional

medicinal plant species in

countries visited during this

survey.

1.

COTE D’IVOIRE (see Ake-Assi,

1988)

EXTINCT IN THE WILD

- Monanthotaxis capea

(Annonaceae) - aromatic

leaves used for washing

for cosmetic purposes.

VULNERABLE AND

DECLINING

- Garcinia afzelii

(Clusiaceae) - favoured

and important source of

chewing sticks in Ghana,

Côte d’Ivoire and

Nigeria Garcinia kola

(Clusiaceae) - more

widespread than G.

afzelii, but also heavily

exploited as a source of

chewing sticks (Ake Assi,

1988).

- Okoubaka aubrevillei

(Oknemataceae) - used

symbolically to ward off

evil spirits. Potent

allelopathic effect on

most surrounding plants.

Endemic family to

Guineo-Congolian region.

Potential source of new

and interesting organic

compounds.

NOTES

: Also important are the

following species with medicinal

properties (Ake Assi, 1983; Ake

Assi, 1988): Diospyros tricolor

(Ebenaceae), a source of

naphthoquinones; Rhigiocarya

peltata (Menispermaceae); in the

family Fabaceae; the tree species

Haplormosia monophylla, Loesenera

kalantha (genus Loesnera endemic

to Guineo-Congolian region), and

Afrormosia elata which has been

heavily logged for timber,

Apocynaceae; Strophanthus barteri

and S. thollonii. The status of

Epinetrum undulatum (Ebenaceae),

a rare species occurring in the

mountains near Man, north-west

Cote d’Ivoire whose roots

are used in traditional medicine

also needs to be investigated.

2. ZAMBIA

Although local

over-exploitation of Eulophia

petersiana (Orchidaceae)

(restricted to limestone

outcrops; used as a lucky charm

and for a “swollen

stomach”) and possibly

Selaginella imbricata

(Selaginellaceae) (also a limited

distribution, used as a lucky

charm to prevent one from being

wasteful (particularly with

money) due to the “closed

hand” shape of the leaves)

may occur, and numbers of

Pterocarpus angolensis (Fabaceae)

(roots used to treat diarrhoea

and abdominal pains) have

declined around Lusaka due to

demand for timber, no species are

threatened by the herbal medicine

trade at this stage due to the

low human population density and

relatively small size of the

urban population.

3. MOZAMBIQUE

Local over-exploitation of

some species on Inhaca island,

but as in the Zambian example, no

species known to be threatened on

a national scale due to the

relatively small urban population

and low population density.

4. ZIMBABWE

ENDANGERED

- Warburgia salutaris

(Canellaceae) - only

known at present from a

few small coppice shoots

found in the Mhangura

Forest, Eastern

Highlands, Zimbabwe

(S.Mavi, pers. comm.)

where it was heavily

exploited for commercial

purposes (national trade

to urban centres and

rural TMPs) as well as by

guerillas sheltering in

the forests during the

war, as access to

pharmaceutical medicines

very limited. Bark is

used as a panacea for all

ills, and specifically

for headaches, abdominal

pains, an abortifacient

and to treat venerial

disease (Gelfand et al.,

1985). Widely

acknowledged to be

scarce, and probably the

most expensive

traditional medicine sold

in Zimbabwe.

VULNERABLE AND

DECLINING

- Alepidea amatymbica

(Apiaceae) - very limited

distribution in Zimbabwe

(a few localities in the

eastern Highlands, yet

sold in small quantity at

all markets visited

during this survey, where

it is widely acknowledged

to be becoming scarce.

Although this species is

heavily exploited in

South Africa, leading to

local disappearance of

this resource in some

cases, it is far more

widespread there than in

Zimbabwe.

NOTES

: Spirostachys africana

(Euphorbiaceae) (wood burnt and

smoke inhaled to drive away bad

spirits) was also regularly

mentioned by herbalists during

this survey as a species that was

becoming scarce. This is a

reflection of the limited

distrubition of this tree in

Zimbabwe, although the species is

widespread in southern Africa.

Local over-exploitation due to

demand for the timber is a more

likely threat than the herbal

medicine trade. Of more concern

in terms of local depletion of

stocks is the commercial scale

collection of Erythrophleum

sauveolens (Fabaceae) bark for

sale in Mbare market, Harare as

the species is limited to the

eastern section of Zimbabwe. It

is also a highly toxic species

which is used as an ordeal

poison. The status of Phyllanthus

engleri (Euphorbiaceae)

populations also needs

investigation,as this is a high

priced species mentioned by a few

herbalists as being scarce.

5. SWAZILAND

VULNERABLE AND

DECLINING

- Warburgia salutaris

(Canellaceae) - used for

coughs, colds, upset

stomach and as a snuff

for headaches.

- Alepidea amatymbica

(Apiaceae) - used for

coughs and colds.

- Siphonochilus aethiopicus

(Zingiberaceae) - used

for coughs and colds, as

well as for proection

against lightning.

All of the above species were

recorded in this survey as being

heavily exploited for local

demand as well as in response to

the urban demand in South Africa.

According to local herbalists,

Siphonochilus aethiopicus has

disappeared from known localities

outside Malolotja Nature Reserve,

Swaziland.

6. MALAWI

VULNERABLE AND

DECLININ

- GDioscorea sylvatica

(Dioscoreaceae)Cassia

species (known locally as

muwawani) - used for

stomach ailments and to

treat venereal

disease.Local

over-exploitation of

Erythrophleum suaveolens,

Erythrina abyssinica

(Fabaceae), and an

unidentified species

known locally as kakome

is an emerging problem.

7. SOUTH AFRICA

(Cunningham, 1990)

EXTINCT IN THE WILD

- Siphonochilus natalensis

(Zingiberaceae) - note

that although this

species is listed

separately to

Siphonochilus aethiopicus

(Zingiberacae) in the

latest national plant

list (Hardie, 1963), the

two species are now

considered to be

synonymous (R M Smith;

pers. comm).

ENDANGERED

- Warburgia salutaris

(Canellaceae) - used for

coughs, colds, as a snuff

for headaches (powdered

bark mixed with bark from

Erythrophleum lasianthum

(Fabaceae).

- Siphonochilus aethiopicus

(Zingiberaceae) - used

for coughs and colds, to

treat hysteria,

“sprinkling

medicine” for good

crops and to keep away

lightning.

VULNERABLE AND

DECLINING

- Dioscorea sylvatica

(Dioscoreaceae) - tuber

used as a douche for

swollen udders of cattle,

for chest complaints and

for magical purposes.

- Bersama tysoniana

(Melianthaceae) - bark

used by diviners together

with saponin rich species

such as Helinus

integrifolius in an

ubulawu mix to enable

them to interpret dreams

clearly.

- Ocotea bullata

(Lauraceae) - used for

symbolic purposes to make

a person “smell and

become unpopular”.

- Ocotea kenyensis

(Lauraceae) - use as

above.

- Curtisia dentata

(Cornaceae) - red

coloured bark used for

magical purposes. Use

unknown and kept very

secret.

- Pleurostylia capensis

(Celastracaeae) - use

unpublished.

- Faurea macnaughtonii

(Proteaceae) - bark used

to treat menstrual pains,

also for tuberculosis.

- Loxostylis alata

(Anacardiaceae) - use not

recorded.

- Mystacidium millarii

(Orchidaceae) - not a

species specific use.

Common Mystacidium

capense not distinguished

by herbalists as

different. Both species

(and many other epiphytes

used for symbolic

purposes).

- Ledebouria hypoxidoides

(Liliaceae) - bulbs used

to prepare enemas.

NOTE

: Traditional medicinal plants in

other categories are given in

Cunningham 1988b; 1990.

Particularly noteworthy are

Anemone fanninii (Ranunculaceae)

and Stangeria eriopus

(Stangeriaceae), endemic to

south-eastern Africa (declining).

|

Conditions

for cultivation as an alternative source

of supply

Commercial gatherers of medicinal

plant material, whether for national or

international trade, are poor people

whose main aim is not resource management

but earning money.Cultivation as an

alternative to over-exploitation of

scarce traditional medicinal plants was

suggested over 50 years ago in South

Africa for scarce and effective species

such as Alepidea amatymbica (Gerstner,

1938) and Warburgia salutaris (Gerstner,

1946). Until two years ago, no large

scale cultivation had taken place. There

are two main reasons for this, and both

apply elsewhere in Africa:

(1) lack of institutional support

for production and dissemination of

key species for cultivation;

(2) the low prices paid for

traditional medicinal plants by

herbal medicine traders and urban

herbalists.

If cultivation is to be a success as

an alternative supply to improve the

self-sufficiency of TMPs and take

harvesting pressure off wild stocks, then

plants have to be produced cheaply and in

large quantity. Any cultivation for urban

demand will be competing with material

harvested from the wild that is supplied

onto the market by commercial gatherers

who have no input costs for cultivation.

Prices therefore increase with scarcity

due to transport costs, search time and

the long-distance trade.

At present, low prices (whether for

local or international pharmaceutical

trade) ensure that few species can be

marketed at a high enough price to make

cultivation profitable. Even fewer of the

potentially profitable species are in the

category most threatened by

over-exploitation.At present, cultivation

of herbs and medicinal plants is chiefly

restricted to temperate areas (Staritsky,

1980) and with the exception of India

(Kempanna, 1974) and Nepal (Malla, 1982),

few tropical countries have investigated

the potential of cultivating medicinal

plants on a commercial scale. Cultivation

of herbs and medicinal plants is

widespread in eastern Europe, but even

where cultivation is well developed, such

as in the Russian Federation, about half

of the supplies are gathered from wild

populations (Staritsky, 1980). In all

cases where cultivation has taken place,

whether in Europe, Asia or Africa, plants

have been grown for profit or a high

level of resource returns (e.g. multiple

use species for fruits, shade and

medicinal properties) and are either fast

growing species, or plants where a

sustainable harvest is possible (e.g.

resins (Bosweilia), leaves (Catha

edulis).

With few exceptions, prices paid to

gatherers are very low, taking no account

of annual sustainable off-take. In many

cases, medicinal plants are also an open

access, rather than a limited access or

private resource. To make a living,

commercial medicinal plant gatherers

therefore “mine” rather than

manage these resources. If cultivation of

tree species is to be a viable

proposition as an income generating

activity then either:

(1) the flood of cheap bark/roots

“mined” from wild stocks is

reduced through better protection of

conserved forests in order to bring

prices to a realistic level; or,

(2) wild populations will have to

decline further before cultivation is

a viable option.

Cultivation for profit is therefore

restricted to a small number of high

priced and/or fast growing species (Box

3).

Although some of these species are

threatened in the wild (e.g. Garcinia

afzelii and Warburgia salutaris), low

prices ensure that few slow growing

species are cultivated. With the

declining economic state of many African

countries, it is unlikely that subsidized

production of these species is likely to

occur, and collection of seed or cuttings

for establishment of field-gene banks

(for recalcitrant fruiting species) and

seed banks must therefore be seen as an

urgent priority.

Strong support and commitment are

necessary if cultivation is to succeed as

a means of meeting the requirements of

processing plants for pharmaceuticals

(whether for local consumption or export)

or urban demand for chewing sticks and

traditional medicinal plants. If

cultivation does not take place on a

large enough scale to meet demand, it

merely becomes a convenient bit of

“window dressing”, masking the

continued exploitation of wild

populations. The regional demand for wild

Scilla natalensis (Liliaceae) in Natal,

South Africa is 300 000 bulbs yr-1, all

at least 8-10 years old. On a 6-year

rotation under cultivation at the same

planting densities as Gentry et al.,

(1987) used for Urginea maritima, 70 ha

would be required (Cunningham, 1988a).

Due to their slow growth rates, the

rotational area required for tree species

would be far greater, with total area

dependent on demand.

The success of cultivation also

depends on the attitude of TMPs to

cultivated material, and this varies from

place to place. In Botswana, TMPs said

that cultivated material was

unacceptable, as cultivated plants did

not have the power of material collected

from the wild (F. Horenburg, pers.

comm.). Discussions with some 400 TMPs in

South Africa over a two year period

showed general acceptance of cultivated

material as an alternative. Similarly,

TMPs in the Malolotja area of Swaziland

accepted cultivation as a viable

alternative. In both countries there is a

tradition of growing succulent plant

species near to homesteads to ward off

lightning. Similarly, in Ghana, plants of

spiritual significance such as Datura

metel, Pergularia daemia, Leptadenia

hastata and Scoparia dulcis are tended

around villages. Therefore, although

little is known about attitudes to

cultivation of medicinal plants in west

Africa, it is possible that TMPs would be

in favour of cultivation of alternative

supply sources.

An interesting model is provided in

Thailand where a project for cultivation

of medicinal plant of known efficacy has

been initiated in about 1000 villages and

traditional household remedies, with

improved formulae, are produced as

compressed tablets packed in foil and

distributed to “drug

co-operatives” set up through a Drug

and Medical Project Fund in more than 45

000 villages as well as in community

hospitals (Desawadi, 1991). Wondergem et

al. 1989; WHO, 1977) have already drawn

on the Thailand experience in making

recommendations regarding primary

healthcare in Ghana.E

| Box 3.

Medicinal plant species which are

in high enough demand and short

enough supply to have commercial

production potential. ZIMBABWE

Warburgia salutaris

(Canellaceae)*

Alepidea amatymbica (Apiaceae)

Cassia abbreviata (Fabaceae)

SWAZILAND

(for local market and for export

to South Africa)

Warburgia salutaris

(Canellaceae)*

Alepidea amatymbica (Apiaceae)

Haworthia limifolia (Liliaceae)

Siphonochilus aethiopicus

(Zingiberaceae)

SOUTH AFRICA

Pimpinella caffra (Apiaceae)

Asclepias cucullata

(Asclepiadaceae)

Begonia homonymma (Begoniceae)

Dianthus zeyheri (Illecebraceae)

Plectranthus grallatus

(Lamiaceae)

Haworthia limifolia (Liliaceae)

Boweia volubilis (Liliaceae)

Siphonochilus aethiopicus

(Zingiberaceae)

Warburgia salutaris

(Canellaceae)*

Alepidea amatymbica (Apiaceae)

COTE D’IVOIRE

Garcinia afzellii (Clusiaceae)*

Monanthotaxis capea (Annonaceae)

MALAWI

Cassia (unidentified species

known as muwawani)

Unidentified species known as

kakome

NIGERIA

Garcinia afzelii (Clusiaceae)*

Garcinia mannii (Clusiaceae)*

* trees/shrubs with

agro-forestry potential.

|

|